How to stop your clothes adding yet more plastic to the ocean—and even the air—in the form of microfibres.

The tiny plastic particles permeating the planet

Likely you’ve heard that washing some kind of clothes means inadvertently releasing lots of “microfibres” or “microplastics” into the environment. But why is that a bad thing, how does it work, and what can we do about it? Read on to discover what to do about microfibres in clothing.

What are microfibres?

Synthetic materials used in clothes like polyester, nylon, and Lycra are essentially made from plastic. Plastic doesn’t “biodegrade” or break down in the environment. So in the case of synthetic fabrics, tiny pieces of “microplastics”—more commonly referred to as “plastic microfibres” in fashion—which are thinner than a human hair and often invisible to the naked eye, are released into the air and our wastewater systems, and from there into our rivers and oceans. It’s important to note that microfibres can refer to tiny particles shed from any fabric composition, plastic and otherwise, while microplastics refers only to the plastic-based synthetic shedders.

According to research commissioned by Friends of the Earth, washing one load of synthetic clothes releases millions of microplastics into the wastewater system. But it’s not only washing that causes a problem. In 2020, we found out that polyester garments release microfibres into the air just by being worn. A study in the Environmental Science & Technology journal estimates that total releases from wearing polyester clothes are about the same as those from washing.

Microfibres are thinner than a human hair and are often invisible to the naked eye. They are released into the air and our wastewater systems, and from there into our rivers and oceans.

Why are microfibres a problem?

Once released into the environment, microfibres are a magnet for organic pollutants and absorb toxic stuff from detergents and fire retardant chemicals they meet in the waste systems. Once in the ocean, they are ingested by sea creatures like plankton, who mistake them for food, and then larger fish and whales scoop up the plastic along with their dinner. Eventually, these marine animals are eaten by one particular animal in the food chain: you guessed it, humans. Shockingly, a quarter of the seafood we consume contains microplastics, and this number will only rise if the problem isn’t addressed.

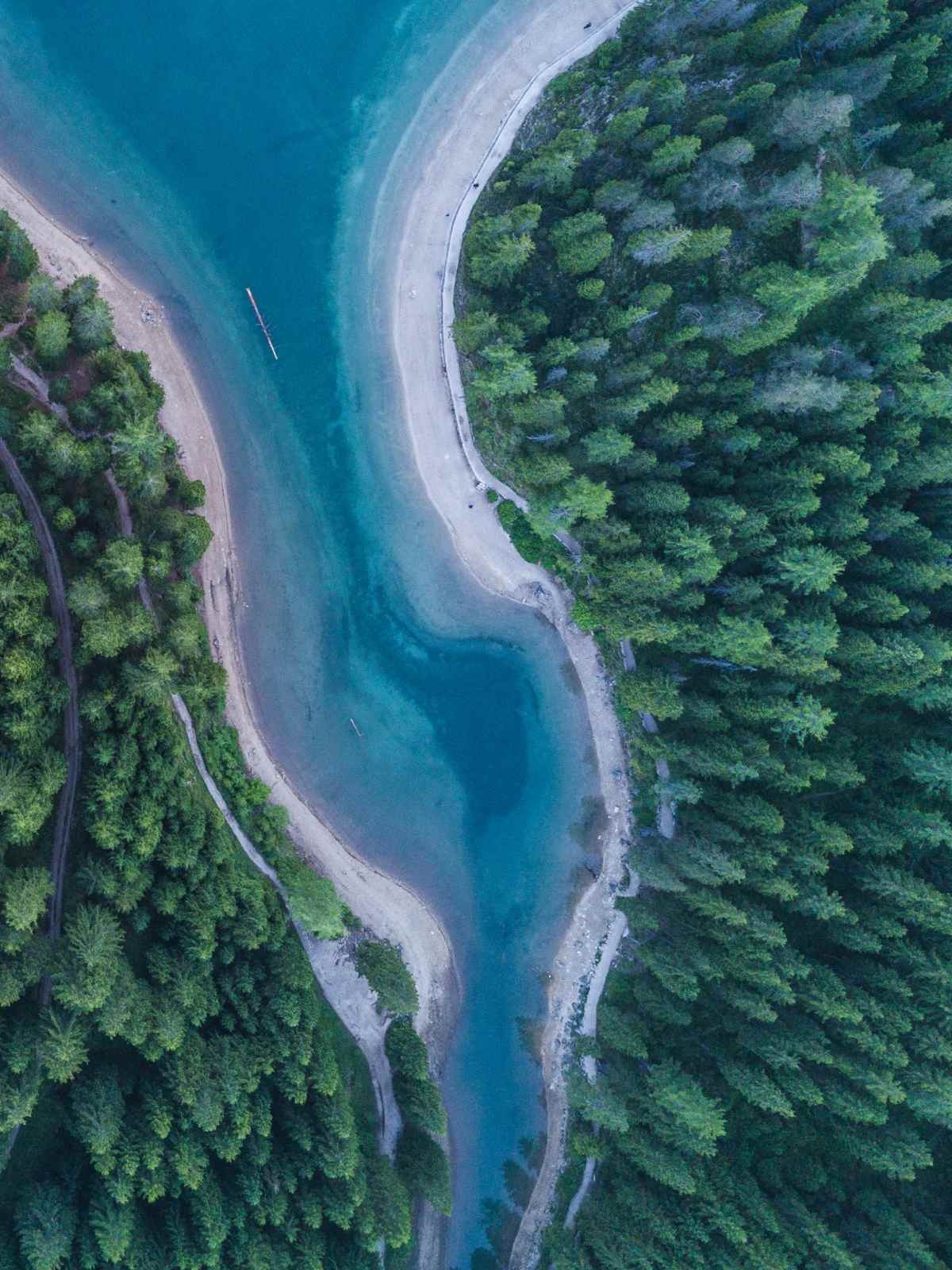

The impact isn’t just significant on people and animals, though. Everything is linked, and sadly the environment also suffers enormously, as microplastics are one of the biggest sources of ocean and shoreline pollution. Not only does this pollution cause a waste problem that won’t go away on its own, but it also absorbs and releases those harmful chemicals we mentioned before, so it’s bad news on top of bad news.

Once released into the environment, microfibres are a magnet for organic pollutants and absorb toxic stuff from detergents and fire retardant chemicals they meet in the waste systems.

Which textiles shed microfibres?

“The shedding of plastic microfibres is a huge concern, but it’s important to remember that all garments—including those made from natural materials and recycled materials—will also shed microfibres during washing and wearing. It should also be noted that microfibres are shed during fabric and garment manufacturing processes, so there is a huge impact here,” says Good On You ratings analyst and materials expert Kate Hobson-Lloyd.

While all fabrics can technically shed microfibres, it’s the non-biodegradable microplastics that we need to watch out for. More than 60% of clothes are made with synthetic textiles derived from oil, like acrylic and nylon (AKA polyamide or PA), but mostly polyester. Fashion brands love them because they are cheap, durable, readily available, and easy to adapt to many purposes. But those synthetic fabrics shed large amounts of harmful microfibres, especially when machine washed with detergent, but also while being manufactured, and even just worn.

Plastic particles washed off from products made with synthetic materials contribute up to 35% of the primary plastic that is polluting our oceans. Every time we do our laundry, an average of nine million microfibres are released into wastewater treatment plants that cannot filter them.

Ocean Clean Wash

Should we just switch to ‘natural’ fabrics like cotton and wool?

Not so fast. Fabrics like cotton, linen, wool, hemp, viscose, modal, and TENCEL are not made from oil and do not shed microplastics. But while these fibres are biodegradable in their untreated state, the application of chemicals and dyes to these fibres has an impact on their ability to biodegrade. And many of them, especially cotton, have other harmful environmental costs. The production of cotton requires large quantities of insecticides and enormous amounts of water. Viscose is made from trees and harsh chemicals—lots of them. And so far, it’s proving much easier to create a circular economy in fashion—one where resources are used over and over again—with synthetics, which are easier to recycle than most natural fibres. The claim that “natural” fabrics are always best for the environment is questionable at best, as every fabric has its pros and cons, though there are of course better options.

Beyond that, there’s little chance that brands and shoppers are going to abandon synthetics anytime soon. For some products, like swimwear and rainproof outerwear, synthetic material is just way more practical and the best option we currently have.

So what can we do to reduce microfibre pollution in the ocean and the air?

Now that we’ve covered the background, it’s time to get practical. Let’s look at what to do about microfibres in clothing on a case by case basis.

Buy less (new) stuff

The number one way to reduce the environmental impact of our clothing choices is to buy less stuff, especially less new stuff. Consider spending (less) of your hard-earned dollars on second hand clothing to extend the life of fabrics already in existence.

Check out The Five Rs of Fashion and Capsule Wardrobes for practical tips on how you can make a difference here but still look great

Choose clothes made from lower-impact materials

Where possible, buy clothes from brands that use the highest level of lower-impact materials, including organic hemp, organic linen, recycled cotton, recycled wool, or the next best options like organic cotton, TENCEL, and Monocel.

If you do choose a synthetic, choose a tightly woven one

An Italian study found that fewer microfibres are released to both the air and in the wash for garments with “a very compact woven structure and highly twisted yarns made of continuous filaments, compared with those with a looser structure (knitted, short staple fibres, lower twist).” This step may be easier said than done, however, and so we’re looking for manufacturers to take note of this advice, change their textile choices to reduce microfibre releases, and communicate what they are doing to shoppers.

Change how you wash

You likely own clothes made with synthetics, particularly swimwear and activewear, and maybe basics, warm underwear, outerwear, and more. Unfortunately for consumers, it’s machine washing that causes the most problems. Here are some useful tips to change up your washing habits and minimise the number of those pesky microfibres being released by your clothes.

- Hand wash where that’s an option, such as removing a stain on otherwise good to go jeans.

- Use a shorter washing cycle at a lower temperature (often marked “eco”). The longer the wash, the more time for microplastics to be released. This step is a bonus for climate change and your budget.

- Wash similar textiles together. Fibres can be released as tougher fabrics rub up against softer ones.

- Wash less often. You’d be surprised how much odour is reduced by simply hanging whiffy clothes in the sun for a while.

- Do full washes rather than half full washes, as less space allows less friction which is helpful here.

- Use liquid detergent instead of powder—another thing to help with that friction.

- Make sure you throw out your lint filters in the trash rather than down the sink.

What about washing machine filters, bags, and balls to catch microfibres?

There is talk across the globe of requiring manufacturers to fit microfibre filters to all washing machines before sale, with some rules being set in motion, notably in the UK and Europe. Campaigners are pushing for a new regulation requiring all new washing machines to be fitted with plastic microfibre filters from 2025. However, until such legislation is global, and while many of us own a washing machine already, there are some relatively accessible and affordable options to look into.

The Cora Ball is a pinecone-esque laundry ball that catches microfibres in the wash; the XFiltra, LINT Luv-R, and PlanetCare are filters that attach to the washing machine outflow, and a Guppy bag is a self-cleaning fabric bag made of a specially designed micro-filter material that you wash your clothes in.

Studies suggest that these products reduce microfibre releases to varying degrees. While the Ocean Conservancy working with the University of Toronto found the Cora Ball caught 26% of fibres in the machine, and the LINT Luv-R captured 86% of the rest, a recent peer-reviewed study from the University of Plymouth had different findings. XFiltra stood out, catching the most microfibres at 78%, while the Lint LUV-R and Planet Care filter systems trapped only 25% and 29% of fibres respectively. The stalks of the Cora Ball ensnared 31% of the fibres, though more than one ball could be used. The Guppy bag claims to reduce microfibre releases by 90%, but the same study mentioned above found it collected 54% of microfibres. While the number is significantly lower than projected, it is still the second-highest score, so worth looking into if you can’t fit a filter.

“It’s promising that consumers are gaining awareness of microfibres and that devices such as washing machine filters are becoming more commonplace in helping to tackle the issue,” Hobson-Lloyd shares. But for further impact, she stresses, “it would be great to see more brands participating in initiatives such as The Microfibre Consortium and setting time-based targets around using low-shedding materials.”

Tips for reducing shedding in specific clothes

Recycled synthetics

More and more responsible brands are using fabrics like ECONYL and Repreve made from recycled plastics from PET bottles or fishing nets rescued from the ocean.

Reusing resources is good for the environment—generally, the impact on many environmental dimensions is much lower than sourcing new. But a fleece made from recycled polyester will still release microfibres, so follow the washing steps mentioned earlier and consider popping the garment into a washing bag.

Swimwear

The most common fabrics for close-fitting swimwear are nylon blends, typically 80% nylon, 20% elastane/spandex/Lycra to give stretch. Nylon blends are soft, comfortable, form-fitting, and dry quickly.

Competitive swimwear is more likely to be made from polyester blends, as is swimwear with prints—it’s much easier to print on polyester than nylon.

You could always look for non-synthetic swimwear, but cotton doesn’t wear that well in harsh environments like pools and the sea, and poly-cotton blends still release microfibres.

Luckily the best way to look after your swimwear—gentle handwashing—is the best way to reduce microfibre release, too. It also makes the most sense since swimwear is often worn for a short period and should rarely require a machine wash.

Fleece, faux fur, acrylic knits, and other products with loose fibres

Avoid machine washing these heavy-shedding synthetics where possible. Spot clean any fleecy garments when you can.

Activewear

Activewear is tricky, as it is almost always made of synthetic, plastic-shedding fabrics and is usually the type of clothing that needs the most washing. We are still hanging out for fabric innovations here, but until then, consider buying recycled plastic versions to reduce some impact and washing in a Guppy bag. It’s worth looking into TENCEL activewear as a lower-impact alternative, and other non-polyester based activewear by better brands.

Older synthetics

There’s evidence that older synthetic clothes shed more microfibres. By all means, get your 30 wears, but maybe not 130 wears unless they can be spot cleaned, as mentioned above. The good thing about purchasing long-lasting, more sustainable clothing now means that when it comes time to say a final goodbye to, for example, your favourite 100% organic cotton top, you can compost it.

Biosynthetics

Biosynthetics are made entirely from natural sources but have some of the desirable properties of synthetics. As they’re not made from fossil fuels (plastic), there are zero plastic microfibres. However, despite being derived partly from bio-based raw materials, bio-based polyester is ultimately still polyester and is not biodegradable. In terms of a practical, commercially available product, we’re not quite there yet. Watch this space.