Our editors curate highly rated brands that are first assessed by our rigorous ratings system. Buying through our links may earn us a commission—supporting the work we do. Learn more.

To meet the demand of fast fashion’s ever-changing window displays, fashion as we know it has been increasingly reliant upon low-cost labour. Here’s how it affects garment workers.

A labour-dependent industry

Every year, we collectively purchase tens of billions of pieces of new clothing globally. A McKinsey and Company study found that fashion consumption increased by 60% between 2000 and 2014 alone. By 2030, it is estimated the fashion industry will consume resources equivalent to two Earths, with the demand for clothing forecast to increase by 63%.

Who’s making all these clothes? Well, fashion is one of the most labour-dependent industries because each piece of apparel must be handmade along a lengthy supply chain, thanks to millions of garment workers (a majority of those workers are female) worldwide. And to increase profit, fast fashion has been increasingly reliant upon low-cost labour in low- to lower-income countries (LMIC) like Bangladesh, India, China, Vietnam, and the Philippines. This practice, known as “offshoring”, began decades ago, with the fall of powerful labour unions in places like the US and the rise of globalisation.

As a result of offshoring, women workers have entered the industrial workforces of production countries at ever higher rates. Several studies have documented this phenomenon, termed the “feminisation of labour”, a term not only used to define the sharp increase in women’s labour force participation in industrial sectors but also to underscore the deteriorating nature of such employment. For these women, work is increasingly precarious and unpredictable. “People used to import slaves to their rich countries, but right now we are being enslaved within our own communities, through the globalisation of our supply chain,” said former child labourer in a Kathmandu garment factory, Nasreen Sheikh, to Fashion Revolution.

This globalisation of supply chains has led to some of the worst exploitation in the fashion industry, where garment workers—many of whom are women—suffer under the tyranny of big brands that treat them like mere commodities. This makes fast fashion a hot-button feminist topic when considering the implications of employing so many women in an unregulated labour market.

The realities of unsafe workplaces

Workers’ rights violations are commonplace in factories for fast fashion garment workers. And while extreme poverty certainly affects both men and women, women experience many more obstacles in escaping poverty. They often feel unable to organise and advocate for themselves as a group, either due to cultural norms or strict anti-union policies within the workplace. Stories coming out of factories in Bangladesh tell us about women with bladder infections due to a lack of bathroom breaks and managers forcing women to take the contraceptive pill. The lack of a living wage amplifies issues like denial of maternity leave, inadequate sanitation, and sexual harassment in the workplace.

An Oxfam 2019 report also found that 0% of Bangladeshi garment workers and 1% of Vietnamese garment workers earned a living wage. This prevents workers from saving money to have a safety net while looking for alternative employment. Often, women start their daughters working in the factory as young as age ten to help feed their family because one wage is inadequate. Being trapped in this cycle makes women increasingly more susceptible to sexual abuse because they can’t risk the loss of income by reporting misconduct, with 1 in 4 Bangladeshi garment workers disclosing some form of abuse to Oxfam.

Then there’s the real and present threat of death, as shown by devastating disasters like the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh in 2013 (80% of the 1,129 people killed when the factory crumbled were women, along with a number of children), or the recent factory collapse in Casablanca which killed six workers.

The garment industrial trauma complex

When COVID-19 hit, the asymmetrical power relations between brands and suppliers enabled many brands to shirk accountability to workers in their supply chains. This led to widespread wage theft, informalisation, job insecurity, and work intensification, which became particularly pronounced during the pandemic-induced recession. This has had devastating impacts on women garment workers and their families.

A 2021 report by the Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) linked the rise in gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH) during the pandemic to the purchasing practices of international fashion brands, including American Eagle, Bestseller, C&A, Inditex, Kohl’s, Levi’s, Marks & Spencer, Next, Nike, Target, Vans/VF Corporation, and Walmart.

AFWA termed economic harm that is fuelled by corporate greed and the feminisation of labour the “garment industrial trauma complex.” It directly contributes to a complex web of trauma from verbal, physical, and sexual abuse and intersects with heightened health-related anguish, and extreme economic-based anxiety that leads to trauma.

What can consumers do?

In theory, offshoring promised opportunities for women in recently industrialised nations, including better wages, independence, and development. But power imbalances remained, and cheap labour became the name of the game. It’s a system that repeats the same patterns of colonialism, with colonial powers in areas like Europe, America, and Australia profiting off the exploitation of colonised countries.

The reality is dire: according to AFWA, while the global garment industry has promised to reduce poverty and uplift the status of women, in reality, it has delivered rock-bottom wages, extreme hours, and unsafe, often violent conditions to meet these pressures felt throughout the supply chain.

Here’s the truth: when we purchase fast fashion, we are often participating in a system that leads to the chronic exploitation and humiliation of some of the world’s most vulnerable inhabitants. We can’t wait for voluntary measures and empty promises from fast fashion brands. So what can you do?

- Avoid buying from fast fashion brands, and any brand that exploits workers and the planet. Instead, shop your own closet, explore second hand options or support brands that are doing “Great” for people.

- Use your voice. Consumers are also citizens. And in many jurisdictions, the voices of citizens can make a real difference. Writing emails, making phone calls, and asking brands to show public support for new laws. Newer approaches like sharing campaign materials on social media can also influence hearts and minds.

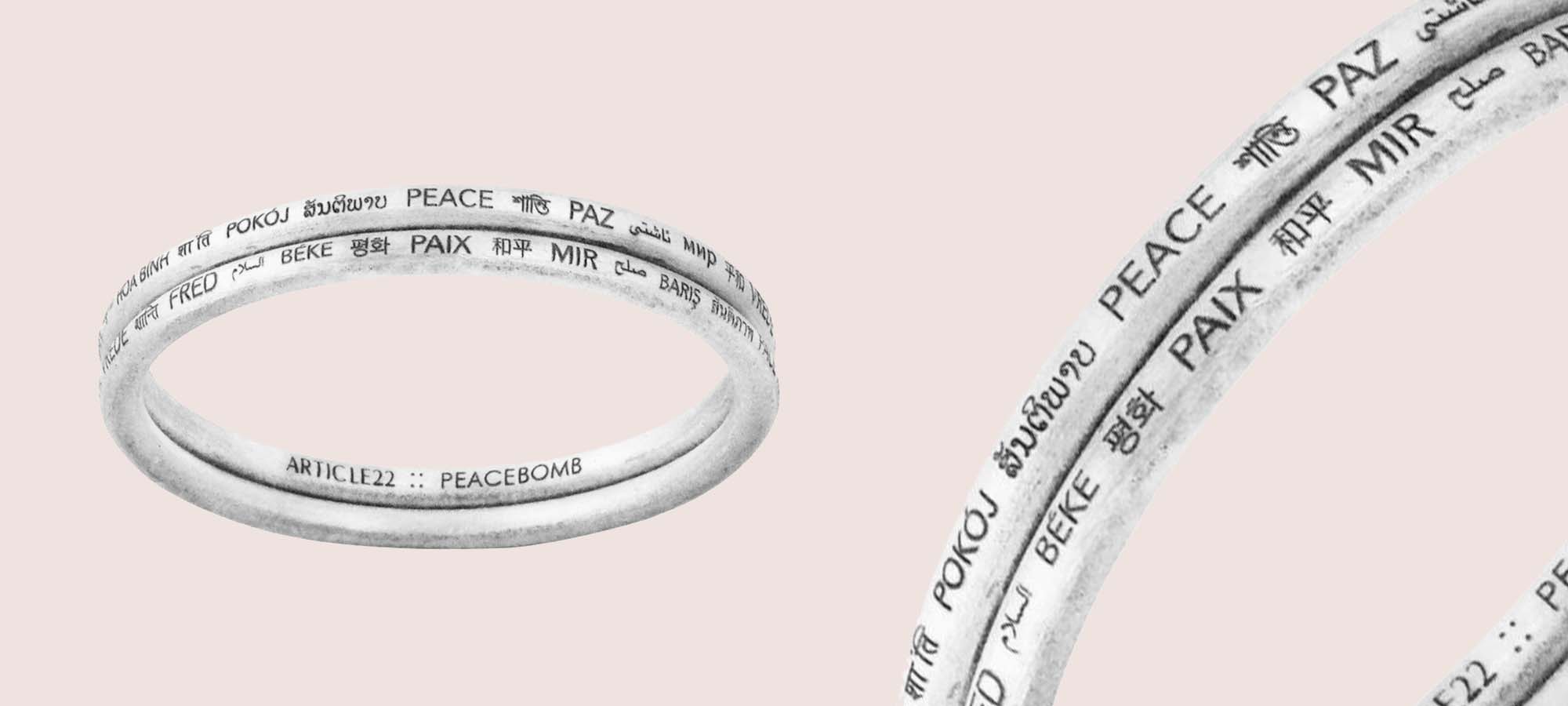

- Good On You believes in supporting companies that protect and nurture employees at all levels of the supply chain. In addition to the brands listed below, check out some of our “Good” and “Great” rated brands to discover the ways some companies are working to support developing economies, protect their workers, and produce clothing that looks good, too.

Turning the industry around

The 2019 State of Fashion report describes a 630% increase in the use of the word “feminist” in brand marketing between 2016 and 2018. The report predicts that moving forward, consumers are increasingly looking for extended corporate social responsibility in the brands they support, with the expectation that companies will disclose their social impact. This is a crucial trend after the devastation of COVID-19 in 2020 that caused another shock to an already fragile system.

Improving women’s access to financial resources, work in the fashion industry could be a tool of empowerment instead of exploitation

According to the UNDP, one of the most effective strategies in international development is to put money directly into the hands of women. The statistic is that for every woman lifted out of poverty, she will bring seven other people over the poverty line alongside her. Good development recognises that women don’t have a knowledge or skills shortage; they just have a cash shortage.

Garment factories that offer a liveable wage and the flexibility to balance a personal life outside of work can go a long way in improving the status of women to meet the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals.

Fortunately, Deloitte Access Economics report for Oxfam in 2017 found that paying a living wage to fast fashion garment workers throughout the supply chain may only increase the retail price of a garment by 1%. Similarly, researchers Hall and Wiedmann found that increasing the cost of clothing made in India by an average of 20c per item would be enough to lift all Indian garment workers out of poverty. This simple step makes fair working conditions a reasonable expectation for consumers.

The importance of uplifting women

Women already run the lion’s share of global businesses and make up the majority of the fashion industry. There is a clear opportunity to give workers greater ownership over the garment-making skills that companies are so eager to source by ensuring women—particularly women of colour—are promoted into leadership roles and included in all decision-making that concerns their livelihoods and wellbeing.

Those currently employed in the industry already know how to run their businesses and understand what workers need. Paying a living wage, providing adequate time off and paid leave, and ensuring strict workplace safety codes within the factory are all good starts. There are existing companies using fashion to provide fair work, such as Dorsu (“Great”) in Cambodia and Mayamiko (“Great”) in Malawi. These companies challenge the myth that the slave-wage business model is the only way to be profitable.