Data analysis by Good On You’s team

The Fashion Planet Benchmark Report reveals the alarming gap between industry action and environmental reality, with major brands scoring just 30% in the planet pillar of Good On You’s brand ratings. These charts highlight critical shortfalls in emissions tracking, supply chain transparency, and circular design—and clearly show where brands can demonstrate leadership.

New data revealed in the first Fashion Planet Benchmark Report

When sustainability appeared on the industry’s radar, fashion brands rushed to set ambitious targets, form coalitions, launch ‘sustainable’ lines, and announce pilot after pilot to trial every new concept or material on the market. For several years, the noise was, frankly, deafening.

In the last year or so, a more worrying trend has emerged. The industry is struggling to keep up with supply chain disruptions, rising costs, geopolitical tensions, and looming regulations, and the consequences are dire. As a journalist, I’ve observed brands quietly rolling back their commitments and delaying ESG target deadlines. Greenhushing, meaning brands avoid communicating about sustainability whatsoever, is now as insidious as the rampant greenwashing we’ve become all too familiar with.

There are big-picture macroeconomic issues that are contributing to fashion’s unimpressive progress, says Sandra Capponi, co-founder of Good on You. “Access to capital, short-term profit pressures, squeezed suppliers, sluggish market conditions, and geopolitical uncertainty all play a role,” she says.

It’s difficult to hold the industry accountable for what it says, or doesn’t say, about its environmental impact. The issue stems from the fact that fashion brands don’t usually operate their own factories or produce their own clothes. This allows them to avoid responsibility for what happens in the making of their products. Fashion brands are experts in marketing and retail, but not necessarily in supply chains and carbon accounting. So while they’re adept at shaping a narrative and selling it to the world in a neat package, sustainability requirements add a challenging new layer of complexity that many established businesses are still struggling to master.

There can be a wide gap between what brands say and what they do. Behind the glossy green veneer, what speaks the loudest is the data. Numbers cut through the noise, exposing the lack of progress, and revealing the true commitments, priorities and ambitions of fashion’s leading brands. “The numbers say it all, sadly the industry is far behind where it needs to be to protect the environment and our future,” says Capponi. “Without stronger action and systemic changes, the industry risks losing the trust of consumers, investors, and regulators—all while undermining the resilience of its own supply chains. Fashion simply can’t continue down this path.”

Without stronger action and systemic changes, the industry risks losing the trust of consumers, investors, and regulators.

Sandra Capponi – co-founder of Good On You

Now, Good On You’s Fashion Planet Benchmark Report shines a light on the biggest planetary issues facing fashion, and how the industry fares. Based on data from thousands of small and large brands from fast fashion to luxury and everything in between, the following 15 insights leave a lot to be desired. They highlight the industry’s adoption of low-hanging fruit—easy wins that don’t meaningfully change the status quo—revealing a pervasive gap of deeper supply chain initiatives. Small businesses tend to fare better, but are limited in their wider industry influence.

After Good On You’s analysts parsed the data (see the report below in 15 charts), I’ve identified three key overarching takeaways about where the industry is failing—and where there’s an opportunity for brands to lead.

Takeaway 1: Fashion is not improving on its overall planet impacts

Before we explore the nuance, let’s get this out of the way: collectively, fashion’s largest brands score dismally in this report. The production of materials and clothing has a wide variety of impacts on the environment that fashion is failing to make a meaningful impact on, including water and chemical use and waste, biodiversity and soil health, air pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions.

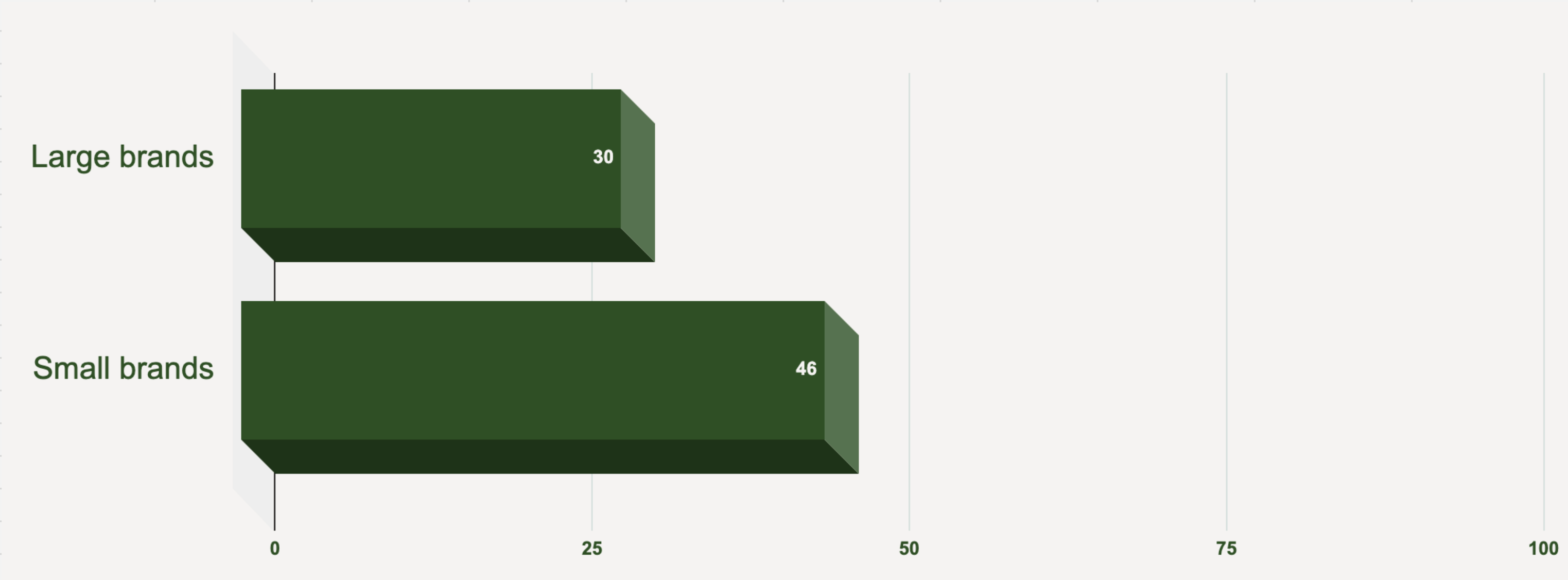

With an average planet score of 30% for large brands and 46% for small brands, it’s clear that the industry is failing to take a holistic approach to impact reduction.

“Fashion companies generally want quantifiable sustainability metrics that offer a clear return-on-investment for shareholders,” says Ruth MacGilp, fashion campaign manager at Action Speaks Louder. “This can mean scrambling for ways to present year-on-year emissions reductions—often through very misleading target setting, carbon accounting, and reporting tactics—instead of making meaningful long-term investments in collaboration with the suppliers actually tasked with implementing change.”

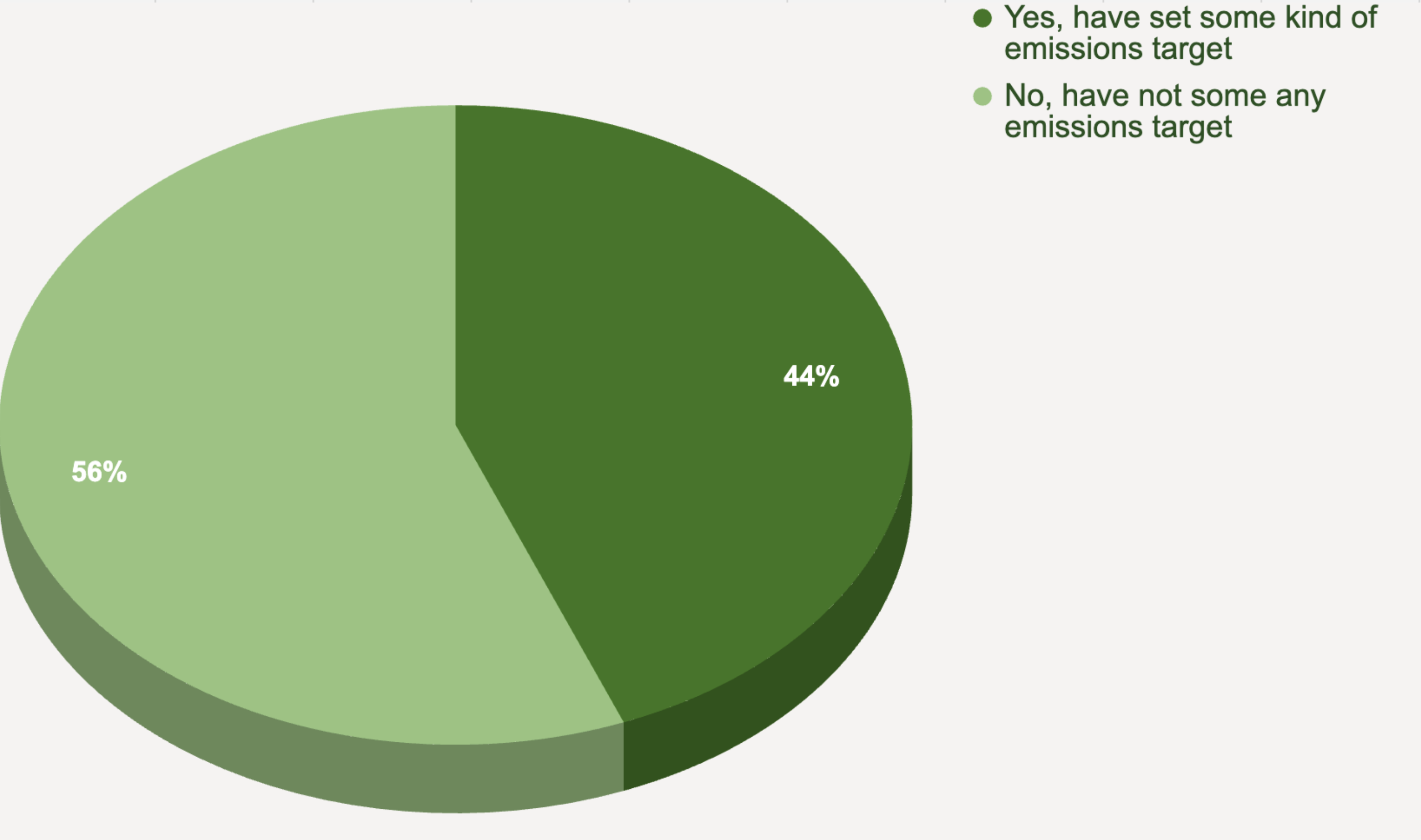

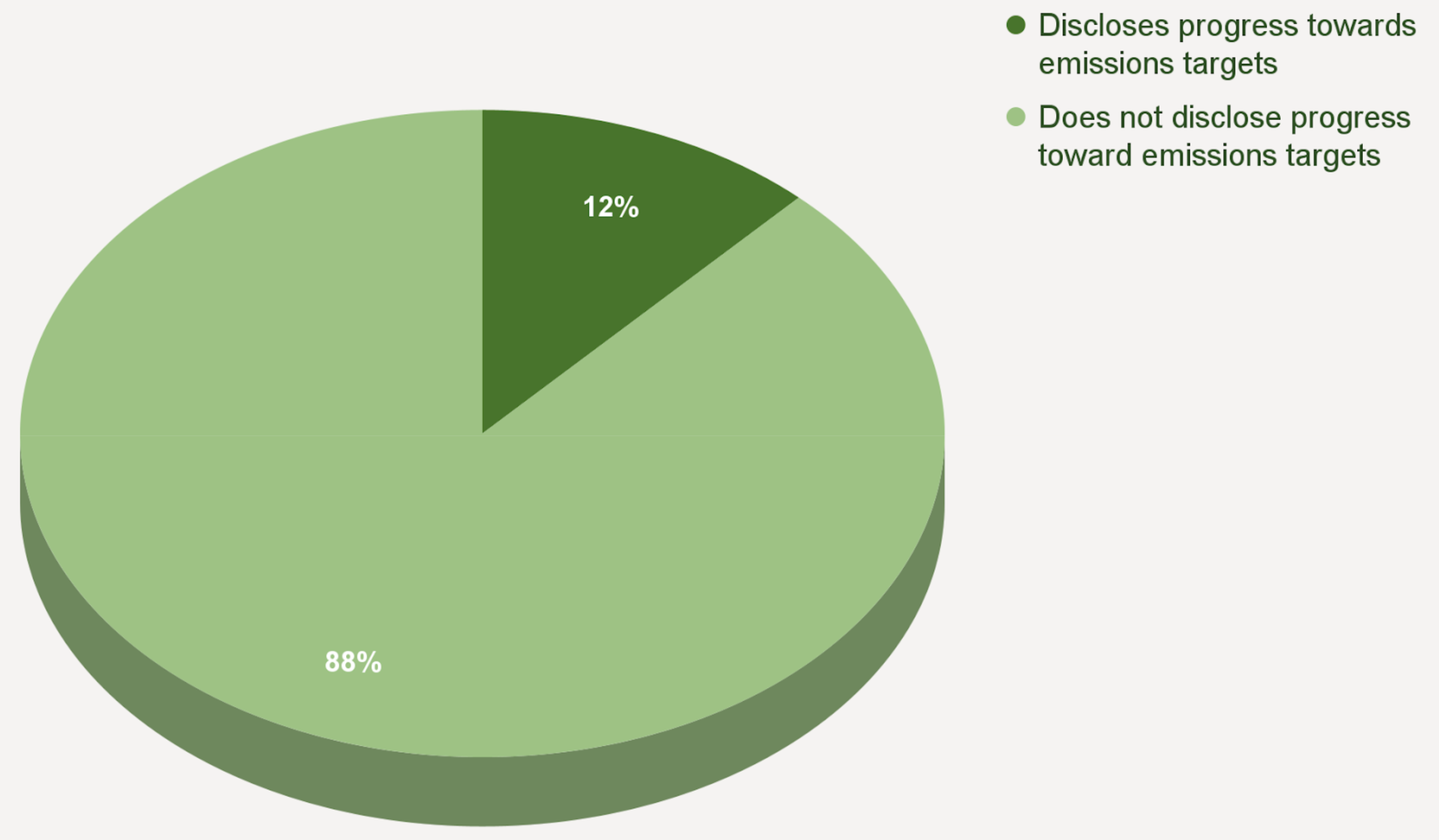

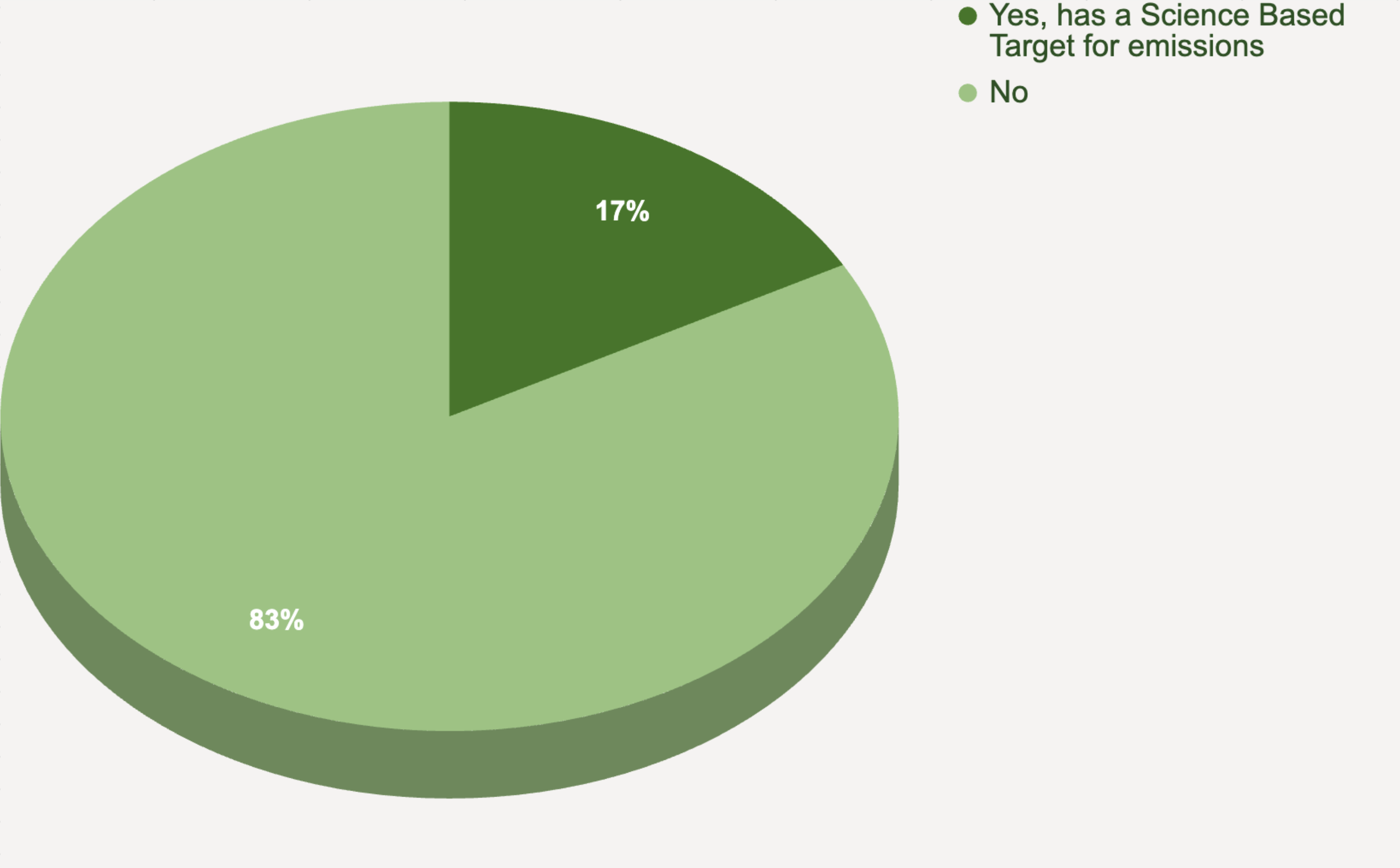

Even brands that have set emissions goals (44% of large brands in this report) aren’t having much impact—the vast majority (88%) of brands that do have targets don’t even disclose whether they’re on track to meet them. Narrowing down even further, only 17% of those targets are science-based and aligned with the Paris Agreement. All of this shows that the industry isn’t serious about emissions reductions, and even less concerned with the nature-based impacts of their operations.

Takeaway 2: Action needs to run deeper in the supply chain

Supply chains are complex and deliberately opaque. To take a raw material and produce a finished product, one piece of clothing can travel across the world and through the hands of dozens of actors. From farmers to raw material processors, dyers, traders, manufacturers, distribution centres, and more, it’s a huge challenge for brands to trace back to exactly where their clothes come from.

Because brands don’t own or sometimes even know the suppliers in their value chains, environmental impact reduction efforts often start as close to home as possible. In measuring emissions, experts refer to scopes. And most brands have measured only scope 1, referring to direct emissions from company-owned and controlled resources, and scope 2, indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy from a utility provider.

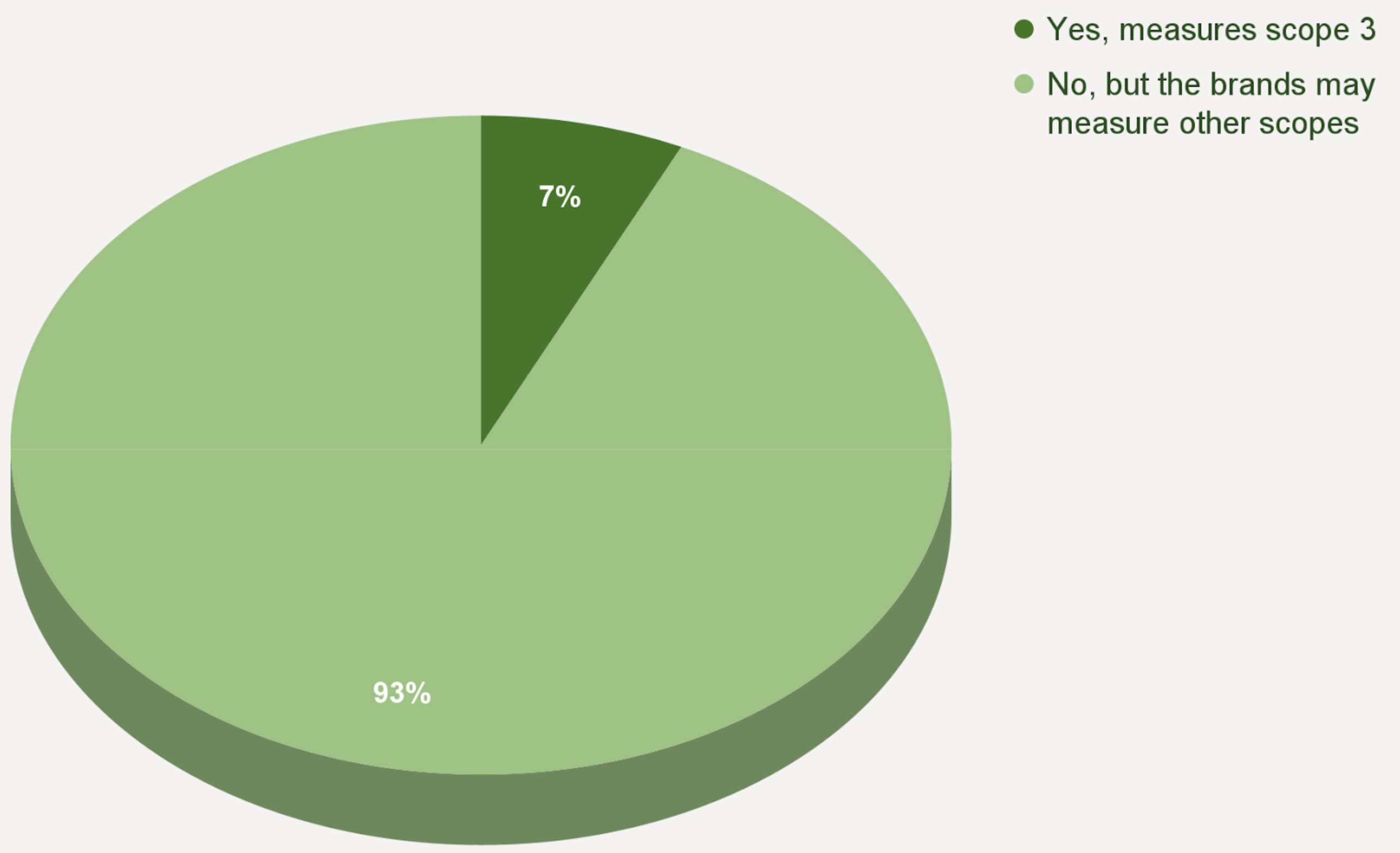

Many large brands are measuring scopes 1 and 2. But according to Good On You’s data, a mere 7% know the emissions from scope 3, which includes raw materials and production. The problem is, the vast majority of a fashion brand’s emissions happen in scope 3.

By only measuring and addressing the tip of the iceberg while ignoring the mass underneath, brands aren’t getting the full picture of their footprint on the planet. It also puts huge pressure and responsibility for decarbonisation on the suppliers who often don’t have the financial capacity to implement this in their facilities. Brands must take more responsibility to collaborate and support their manufacturers and suppliers through this process.

Takeaway 3: Circularity is still a pipe dream

The data shows that circularity is still a long way from a reality for the fashion industry despite growing consumer familiarity with fashion rental, secondhand clothing, repairing and altering, and even in-store take back schemes. At best, 65% of large brands now use recycled polyester (certainly not a perfect solution but a step in the right direction), and at worst, fewer than 40% of all brands are adopting any circularity initiatives, even relatively “easy” ones like rental options (offered by a mere 3% of brands).

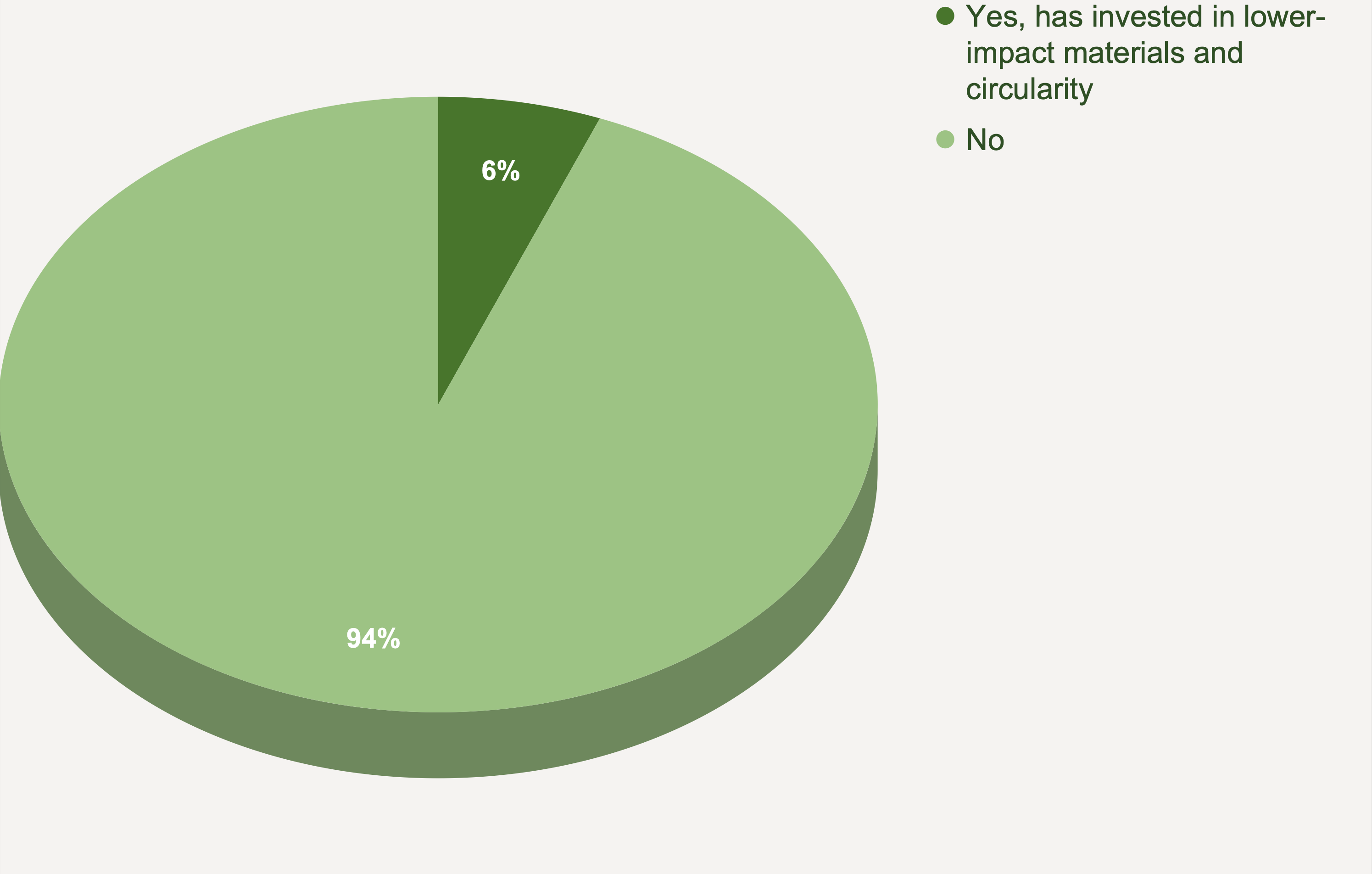

As I’ve mentioned in previous columns, investment is sorely lacking in this industry, and it’s not down to a lack of financial power. Only 6% of large brands report that they’re investing in research and development of circularity. This doesn’t come close to reducing the funding gap of more than a trillion US dollars that has to be filled to meet fashion’s 2030 targets.

A more holistic approach starts with integrating siloed sustainability teams and standalone goals into the business strategy.

Ruth MacGilp – fashion campaign manager at Action Speaks Louder

The outlook may appear bleak, but it’s worth remembering: data can lead to increased accountability and action. Promisingly, there is no shortage of solutions out there for brands to adopt. “A more holistic approach starts with integrating siloed sustainability teams and standalone environmental goals in the wider business strategy, with incentives for executives to prioritise investment in solutions proven to work in the biggest emissions hotspots and that have social and environmental benefits,” says MacGilp.

If we can measure where fashion lacks, we can drill into specific solutions and hold brands to their public promises. “The real responsibility lies with the industry’s biggest players,” says Capponi. “We need the major players to step up and demonstrate what true leadership in fashion looks like. Surface-level emissions reporting and target setting is not enough, and pushing accountability onto suppliers is not the solution either.”

In 15 charts: Fashion Planet Benchmark Report 2025

The following 15 charts spotlight a few of the dozens of issues that factor into Good On You’s comprehensive brand ratings. The insights are based on Good On You’s current database of brand ratings, which includes thousands of large and small brands distinguished based on annual turnover. Learn more about Good On You’s rating methodology and dive deeper into the rating guide here.

A note on methodology and samples before diving in

For this report, we looked broadly for industry trends across the ratings for 1,372 large and 4,032 small brands. (All of these insights are previously unpublished with the exception of figures 12 and 13 below, which look at two stats about emissions targets from Good On You’s COP climate report.) The sample includes virtually every major fashion brand as well as many small labels that show how large brands can do better. The ratings and the insights below are based entirely on brands’ publicly available data, as Good On You only rates brands based on information in the public domain.

Additionally, Good On You’s brand rating methodology factors in lots of different data from a wide range of public sources and weights it all accordingly—from brands’ own sustainability reporting and other public disclosures through to third-party indices, standards, and certifications. Therefore, in some insights below, the sample may zoom in on a specific subset of brands within the wider pool based on the available data from specific sources. For instance, figure 8 depicts steps to cut production/manufacturing emissions, based on brands’ own sustainability reporting. The underlying sample for figure 8 excludes brands that have been graded by CDP, as Good On You’s methodology collects this granular information only when a brand is not disclosing to CDP. Therefore, the smaller sample we’re looking at in those cases is brands’ own disclosures. (The descriptions above the relevant charts include this context.)

Do you work at a fashion brand that’s been rated by Good On You? You can compare your performance to industry benchmarks like these, as well as topics across labour and animal pillars, in the Good Measures tool. Good Measures allows the industry to input data about their sustainability credentials and initiatives, and understand how they compare and can improve. Good Measures collates this data into easy-to-digest statistics, giving a clear picture of the fashion industry’s biggest areas of impact and progress. For the first time, we’re unveiling a few of these benchmarks to the industry at large.

Figure 1: Average overarching planet scores for large and small brands

Good On You’s planet scores indicate out of 100 how a brand performs on average across a range of the most critical environmental issues, including uptake of lower-impact materials, initiatives to reduce textile and non-textile waste, embedding circular design principles in the business model, biodiversity, deforestation, packaging, climate change (emissions reduction, measurement, targets and disclosing progress), chemical use, water impacts, and more. Large brands overall lag behind small brands in average scores, though top performers reveal it’s possible to do better (the top score for a large brand in this sample was 86% whereas several small brands earned 100%).

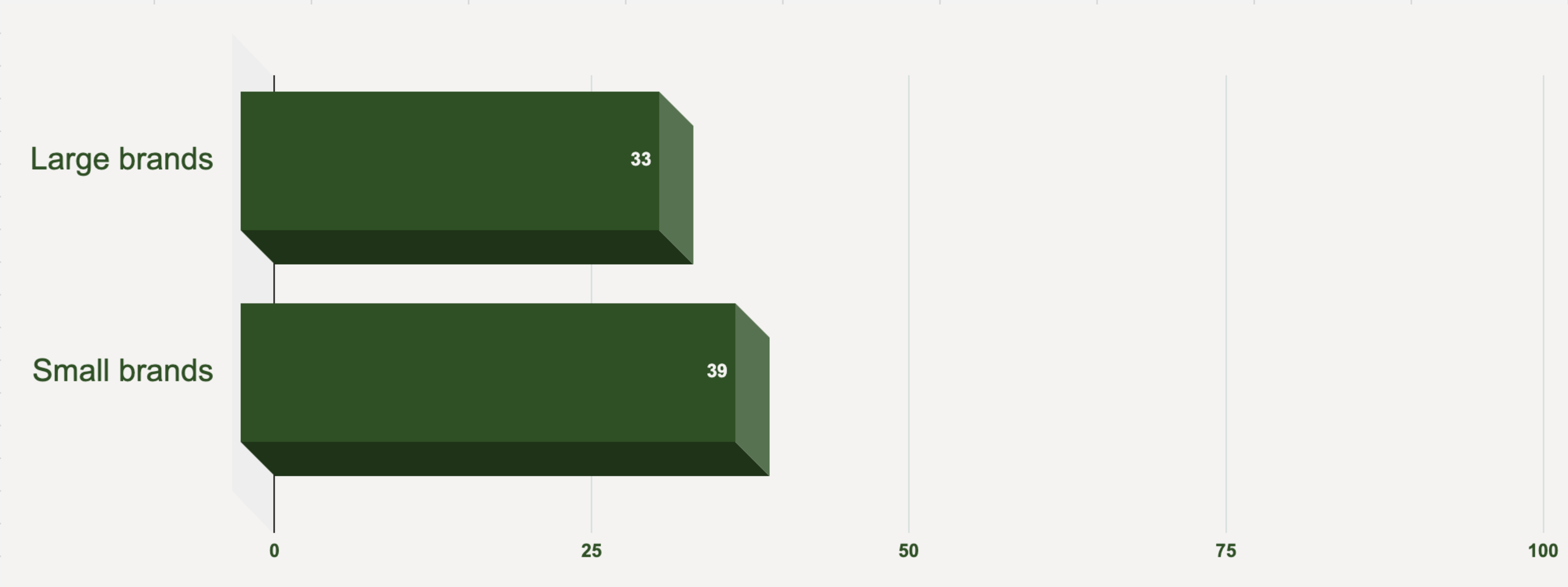

Figure 2: At least one circularity initiative adopted by large and small brands

More brands large and small are beginning to adopt some common circularity initiatives, but this is most often “low-hanging fruit” efforts to reduce waste such as using cut-offs to eliminate as much waste as possible and recycling/upcycling materials within a brand’s own supply chain. However, circular economy advocates debate the extent to which these efforts can help achieve a truly circular fashion economy. Few brands have truly achieved anything resembling circularity at scale, though small brands lead the way in terms of some progress.

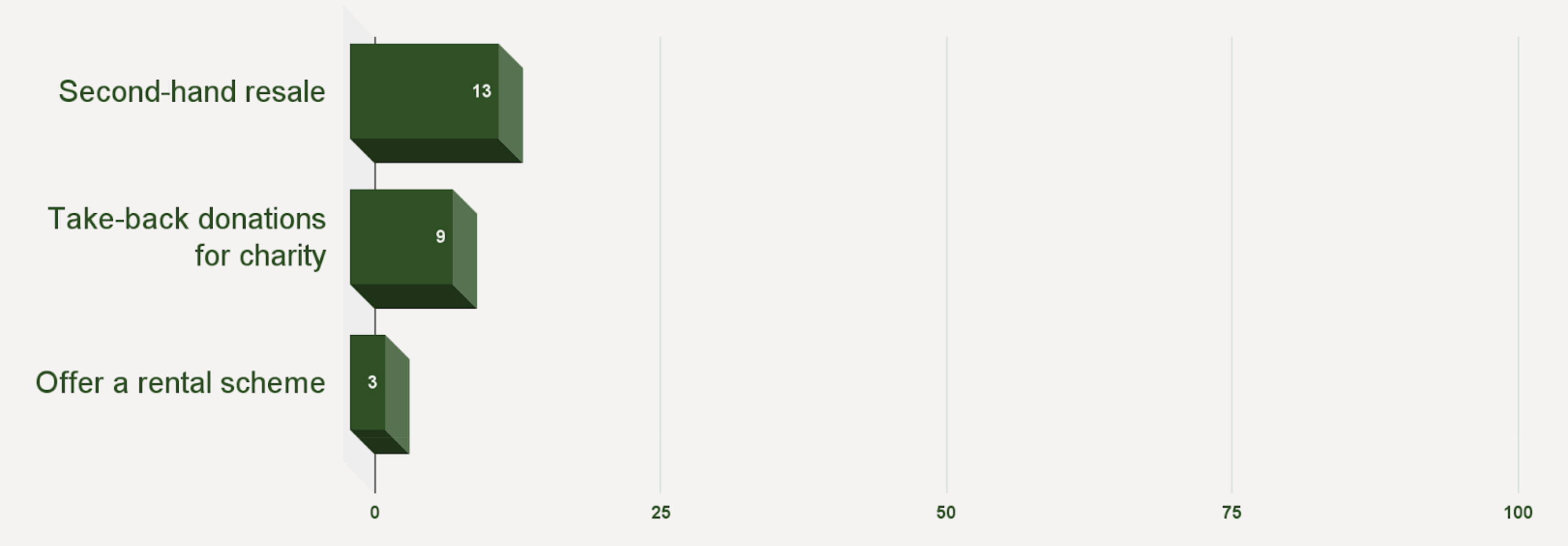

Figure 3: Post-consumer recycling initiatives adopted by large brands

Few large brands are actually implementing post-consumer recycling programs, even arguably easier to implement programs such as second-hand resale. A range of competing start-ups in the secondhand resale space have emerged in recent years, enabling brands of all sizes to offer white-label secondhand resale and rental services. Brands can also forge partnerships with established platforms. And yet, only 13% have resale and 3% have rental schemes. Few even have take-back schemes for charity, which are famously riddled with their own issues, as many charity shops are drowning in cheap fast fashion.

Figure 4: Large brands investing in R&D for materials and circularity

Much of the fashion industry’s impacts are directly related to materials as well as the linear take-make-waste model that is the industry’s status quo. Moving toward lower-impact materials and a circular design economy will require investment in novel and innovative solutions. And yet, most large brands aren’t voting with their wallets for this future, further demonstrating the disconnect between the industry’s actions and the environmental realities.

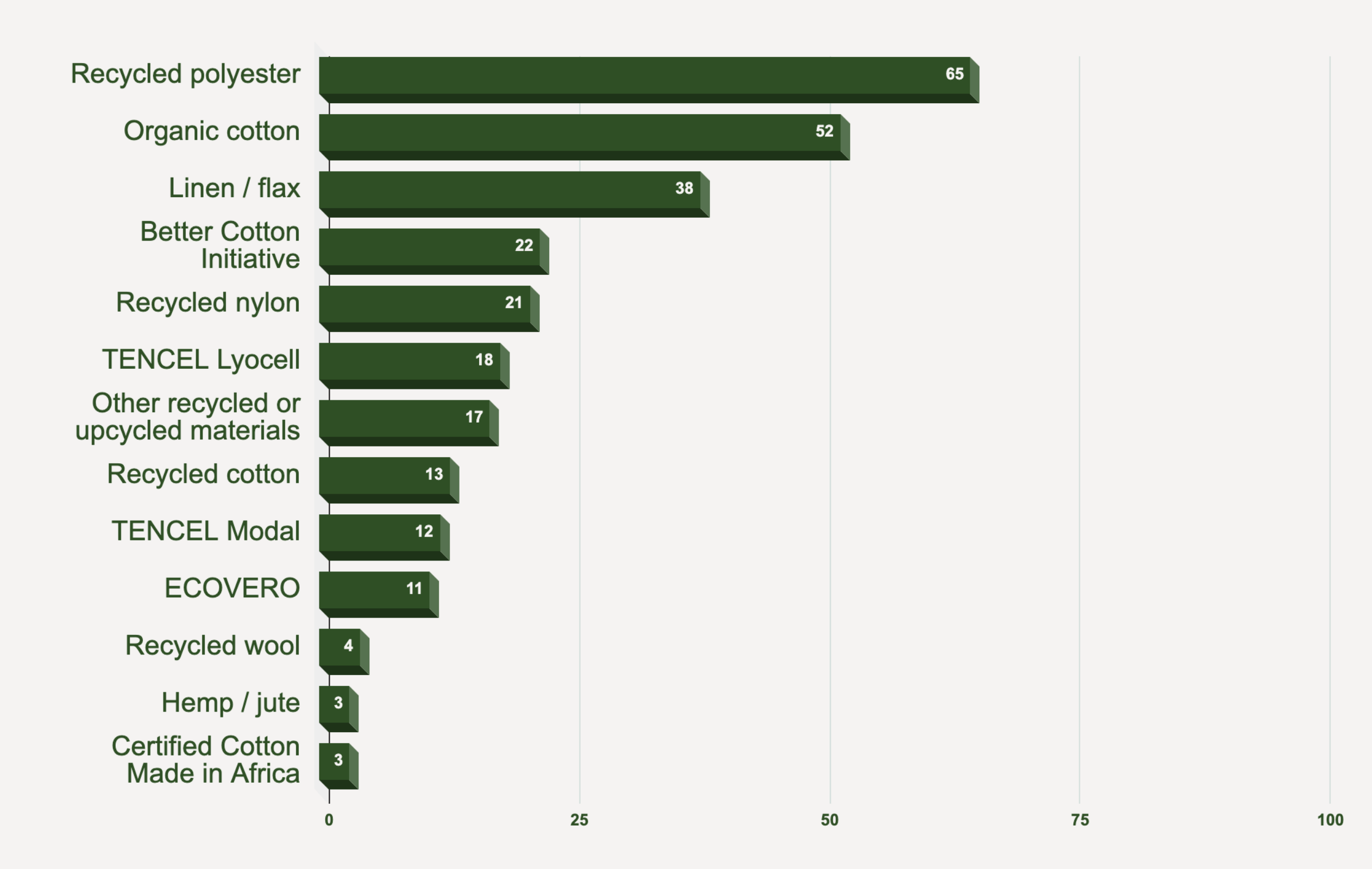

Figure 5: Large brands’ most commonly used lower impact materials

If it feels like most large brands’ “sustainability” actions tend to be the adoption of recycled polyester, you’re not wrong—that’s the most commonly adopted lower impact material by large brands. This chart looks at the sample of large brands that disclose using lower impact materials. (Note: “Other recycled materials” refers to any other recycled materials not included elsewhere on the list, which could include recycled gold, recycled rubber, recycled cashmere. “Upcycled materials” would refer to any materials legitimately considered waste that the brand has turned into a higher-value product. This could include genuine deadstock fabrics, rice sacks, even car parts, and so forth.)

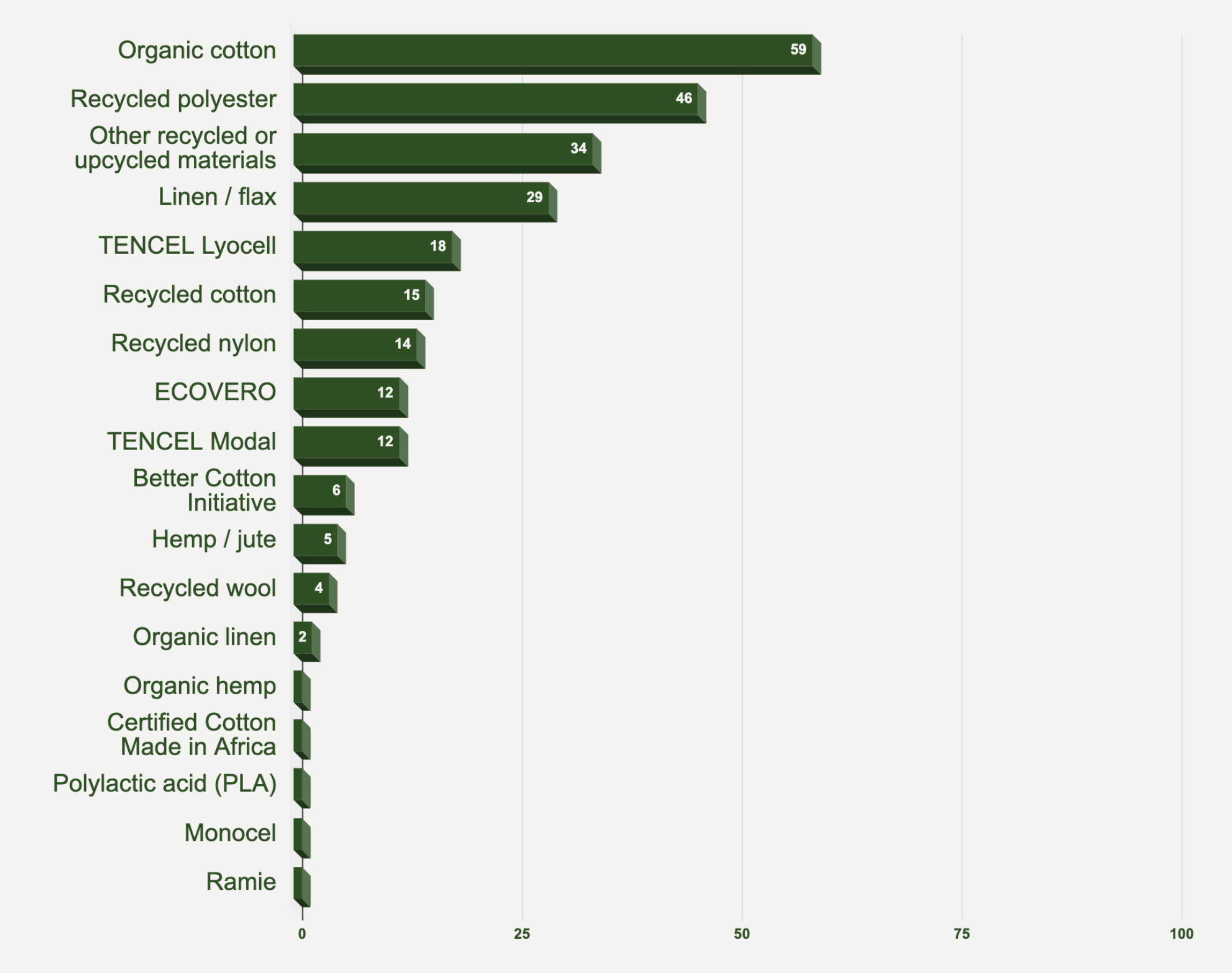

Figure 6: Small brands’ most commonly used lower impact materials

Small brands also commonly report using recycled polyester, but many are also investing in other lower impact materials across organic natural fibres as well as recycled and upcycled materials. This chart looks at the sample of small brands that disclose using lower impact materials. (Note: “Other recycled materials” refers to any other recycled materials not included elsewhere on the list, which could include recycled gold, recycled rubber, recycled cashmere. “Upcycled materials” would refer to any materials legitimately considered waste that the brand has turned into a higher-value product. This could include genuine deadstock fabrics, rice sacks, even car parts, and so forth.)

Figure 7: Many large brands are not measuring scope 3 emissions

Scopes are a way of breaking down where a brand’s emissions occur. Most targets don’t cover the full supply chain. That’s partly because brands aren’t even measuring their full carbon emissions impact across their supply chains. Most large brands have measured their emissions only in scope 1, referring to direct emissions from company-owned and controlled resources, as well as scope 2, ie indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy from a utility provider. Fewer have measured scope 3, where most of their impacts typically occur. Scope 3 means all indirect emissions in the value chain, including both upstream and downstream emissions such as material production and their suppliers’ factories. Note that this chart looks at a smaller sample of large brands based on their own disclosed actions.

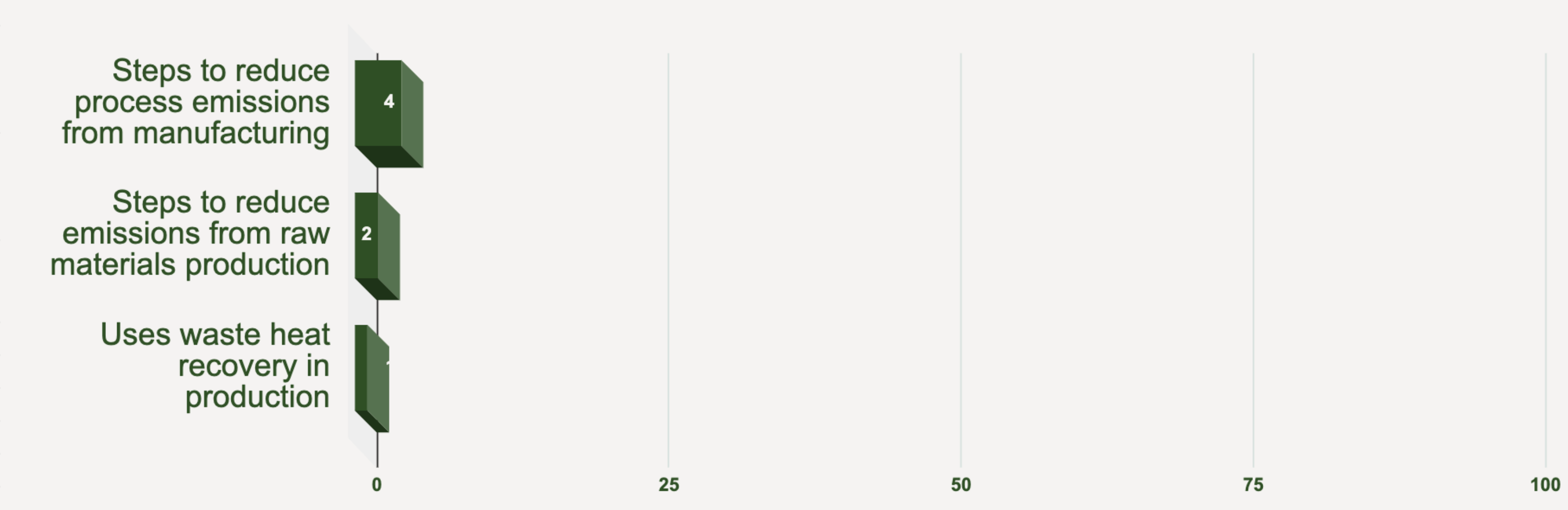

Figure 8: Large brands’ not taking steps to cut production/manufacturing emissions

It’s not easy to reduce emissions. But falling behind on the real threat of climate change also won’t be easy. If large brands actually care about reducing their emissions and future-proofing their businesses, then we’d expect to see them taking steps to do so. And yet when it comes down to it, in the areas of the supply chain that need attention, we don’t see many brands disclosing actions in areas such as cutting production and manufacturing emissions.

Note that this chart looks at a smaller sample of large brands based on their own disclosed actions. The sample for this chart excludes large brands that have been graded by CDP Climate, as Good On You’s methodology collects this granular information only when a brand is not disclosing to CDP, which is one of the primary third-party data sources considered in brands’ planet rating where relevant. Therefore, this chart is based on the data available and what is publicly disclosed.

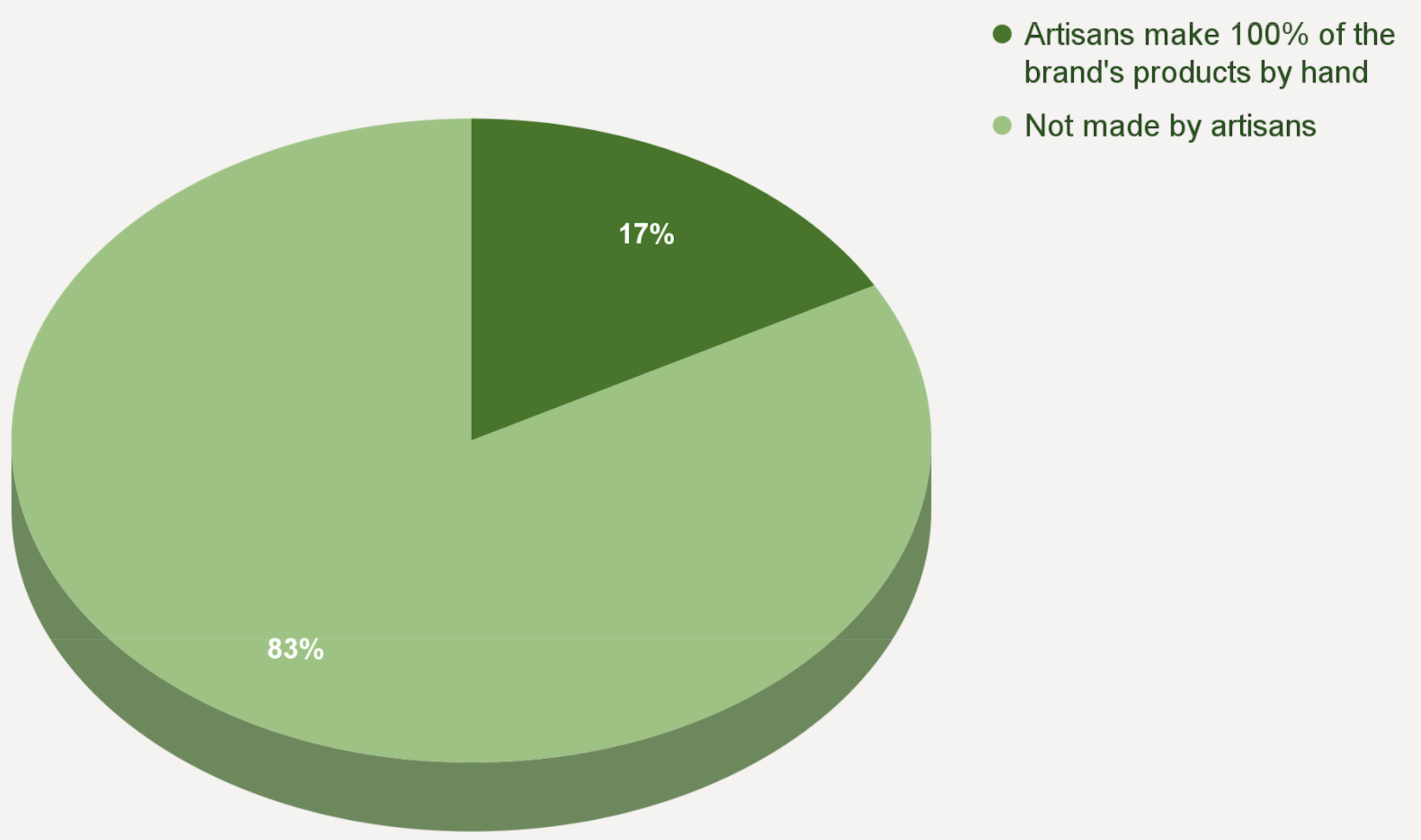

Figure 9: Some small brands work with artisans to cut emissions

When you compare large and small brands’ actions to cut production/manufacturing emissions, you see an interesting distinction: 17% of small brands are working with artisans to make 100% of the brand’s products by hand. Crucially, this means products made without electricity. (Some brands say their products are handcrafted but still require machines that run on electricity.) And creating products entirely by hand without electricity is a great way for brands to reduce their emissions while providing livelihood opportunities as well.

Figure 10: Large brands’ lagging adoption of renewable energy

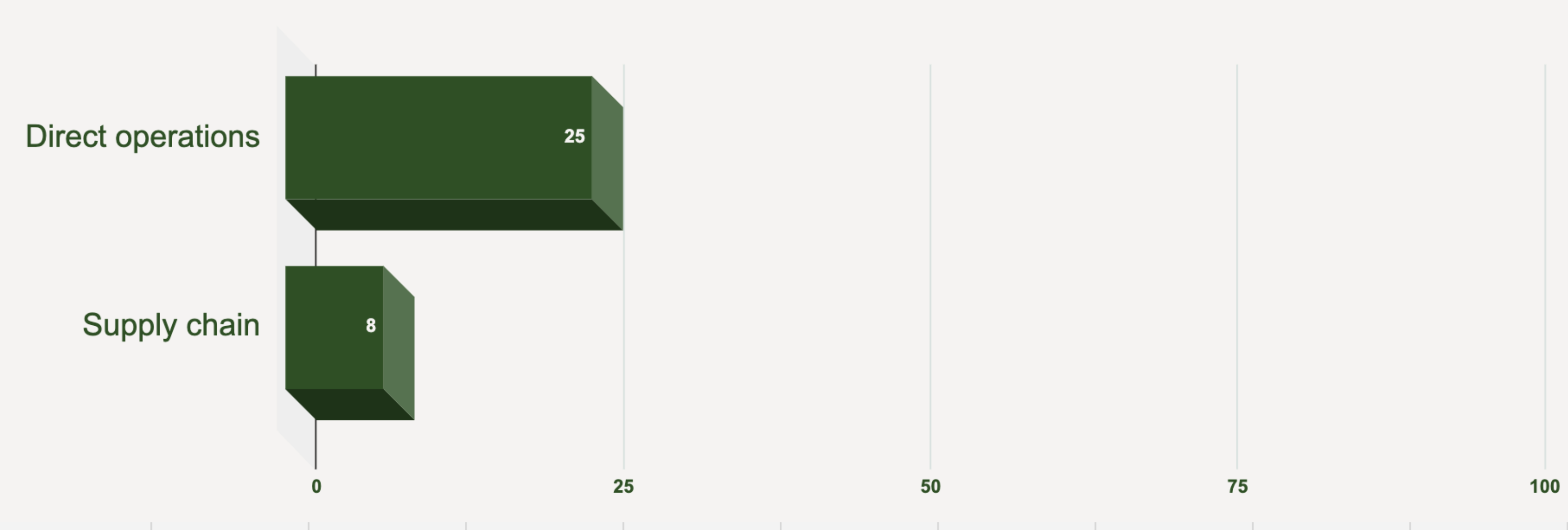

Most brands’ emissions happen in the supply chain, and yet only 8% of large brands have invested in renewable energy in this area. There are numerous reasons why a large brand may be reluctant to fund its suppliers’ adoption of renewable energy. Its suppliers may work with other brands, so who funds the suppliers’ transition? What role can brands play in supporting garment-producing regions in their supply chain for a greener grid, more widely speaking? Those are just a few of the questions facing large brands, who tend instead to invest in renewable energy in their corporate offices and little else.

Note that this chart looks at a smaller sample of large brands based on their own disclosed actions. The sample for this chart excludes large brands that have been graded by CDP Climate, as Good On You’s methodology collects this granular information only when a brand is not disclosing to CDP, which is one of the primary third-party data sources considered in brands’ planet rating where relevant. Therefore, this chart is based on the data available and what is publicly disclosed.

Figure 11: Majority of large brands have not set an emissions reduction target

You’ve heard all the talk in recent years about brands’ targets: why certain targets (like Science Based Targets) are better than others; the fact that few brands are reporting on their progress; and how promoting targets can amount to little more than some positive press. The reality is that more brands are setting at least some kind of target. But the majority of large brands, 56%, have not set any emissions reduction target.

Figure 12: Large brands are not disclosing progress towards GHG targets

Every year, Good On You publishes an annual report about climate change action from fashion brands, timed to the COP summit. In the 2024 report, the data revealed that even among large brands that have set targets, most—88%—are not disclosing any progress towards their emissions reduction targets.

Figure 13: Few large brands have set Science Based Targets for emissions

What are Science Based Targets? Journalist Sophie Benson wrote this explainer in 2022. In short, they represent the “current gold standard” in a largely unregulated industry, Kristian Hardiman, Good On You’s head of ratings, said then. It’s because of this specificity, scientific grounding, and validation that Good On You rewards a “higher proportion of points to brands setting SBTs when analysing GHG emissions,” Hardiman said of Good On You’s brand rating methodology. This stat also comes from our 2024 fashion climate action report.

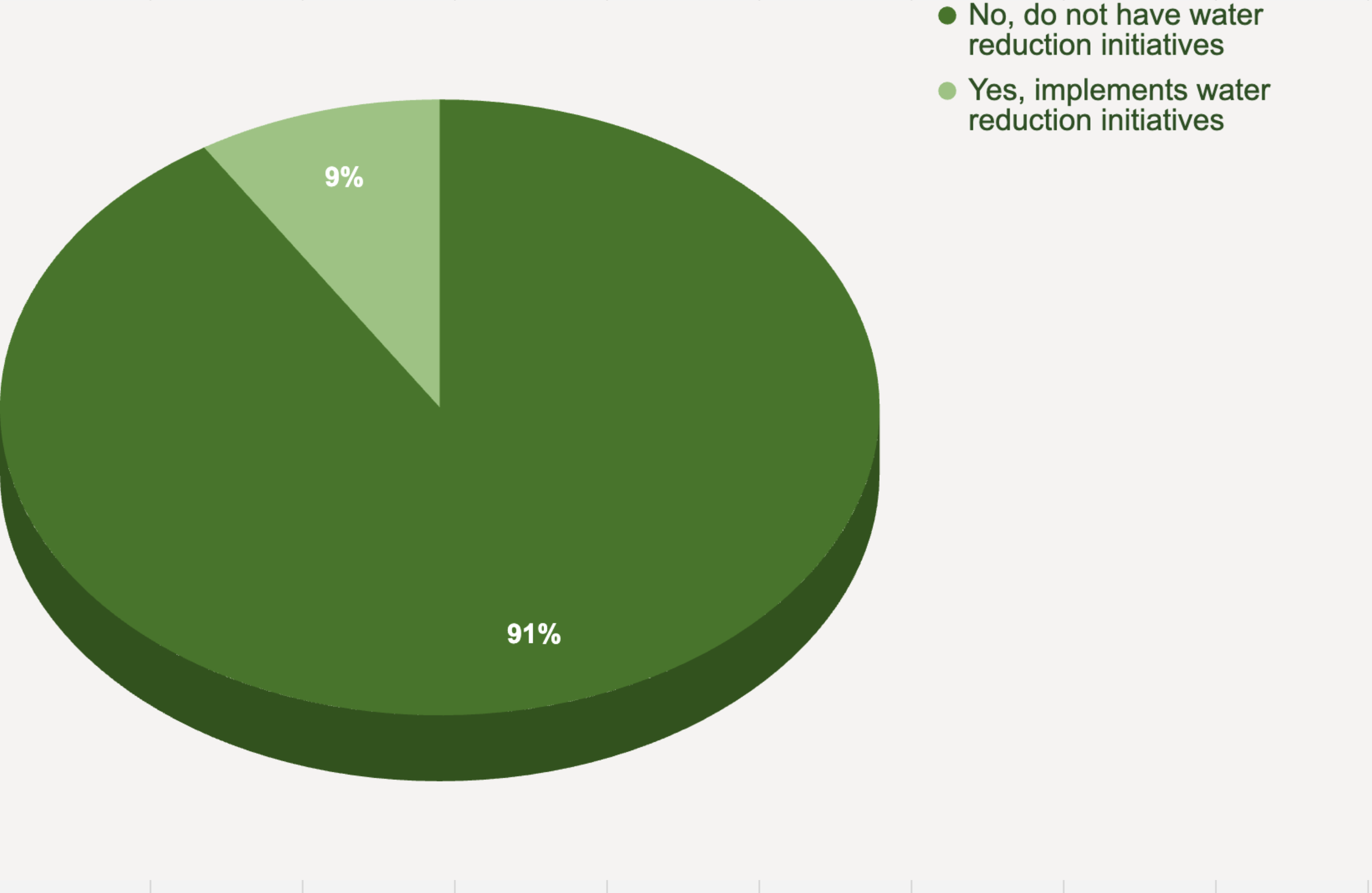

Figure 14: At least one water reduction initiative adopted by large brands

Fashion is one thirsty industry. But most brands aren’t doing much to reduce their water impacts. Again, most of the time that’s because water impacts often need to be addressed deeper in the supply chain, not within a brand’s direct operations. Only 9% of large brands have adopted at least one water reduction initiative.

Note that this chart looks at a smaller sample of large brands based on their own disclosed actions. The sample for this chart excludes large brands that have been graded by CDP Water, as Good On You’s methodology collects this granular information only when a brand is not disclosing to CDP, which is one of the primary third-party data sources considered in brands’ planet rating where relevant. Therefore, this chart is based on the data available and what is publicly disclosed.

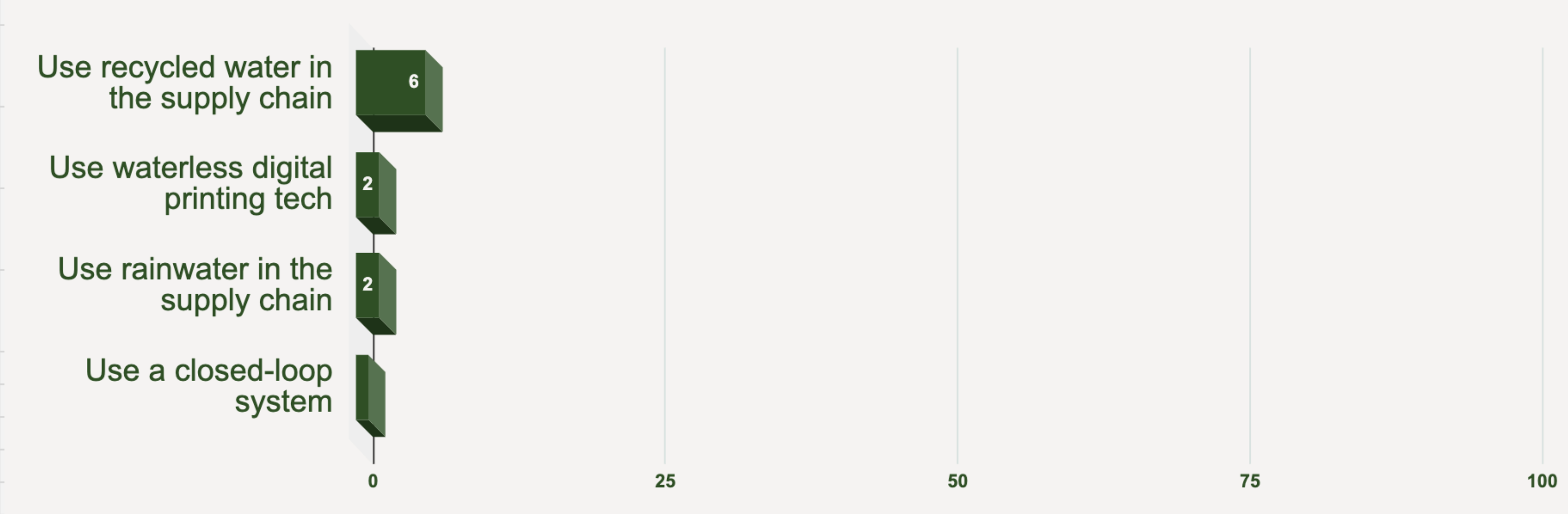

Figure 15: Large brands’ most common water reduction initiatives

Among large brands, analysts have tracked those disclosing only a few water reduction initiatives. Again, only a tiny percentage of brands are actively working with their suppliers to take any action. The most commonly implemented is using recycled water in the supply chain, but only 6% of large brands have done so. Meanwhile, only about 1% of large brands use a closed-loop system.

Note that this chart looks at a smaller sample of large brands based on their own disclosed actions. The sample for this chart excludes large brands that have been graded by CDP Water, as Good On You’s methodology collects this granular information only when a brand is not disclosing to CDP, which is one of the primary third-party data sources considered in brands’ planet rating where relevant. Therefore, this chart is based on the data available and what is publicly disclosed.