Most of the biggest brands aren’t taking urgent action to address their environmental impacts, according to newly released data from Good On You. This report explores the environmental track records for thousands of brands big and small.

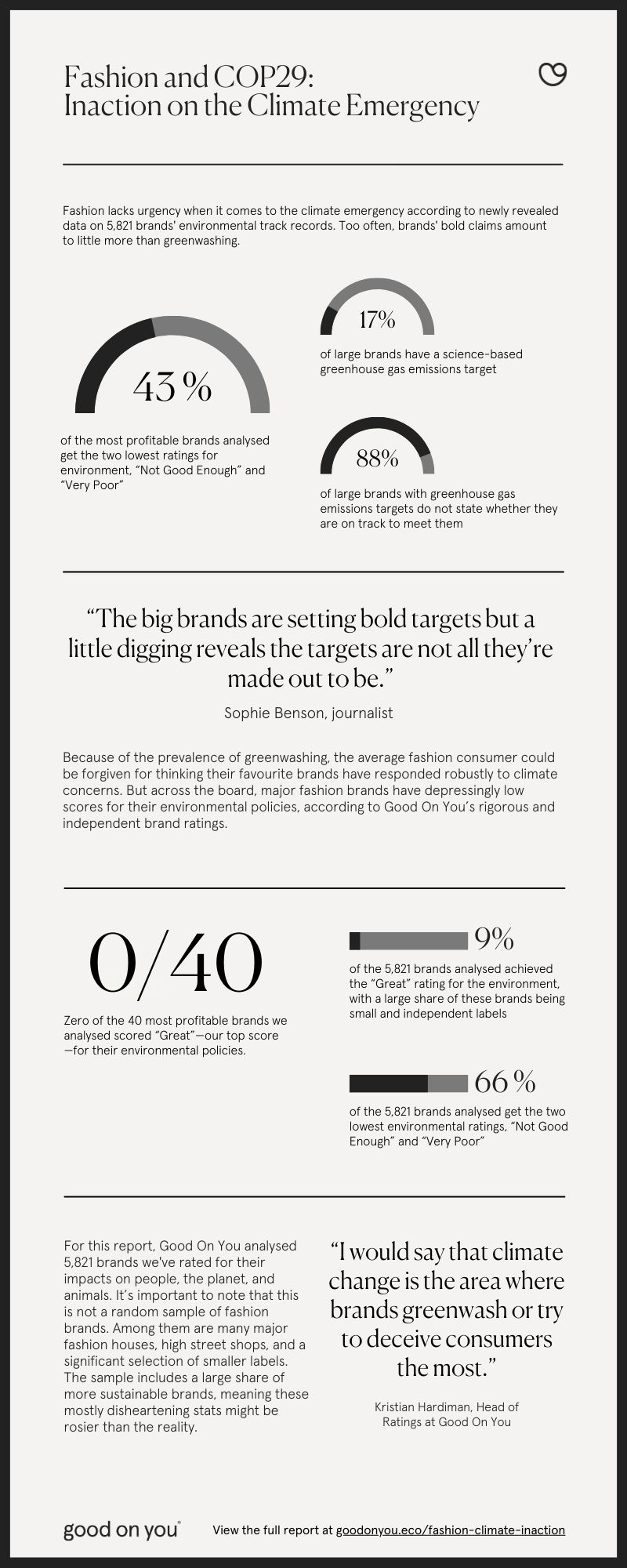

Key stats based on an analysis of Good On You’s ratings for more than 5,800 brands:

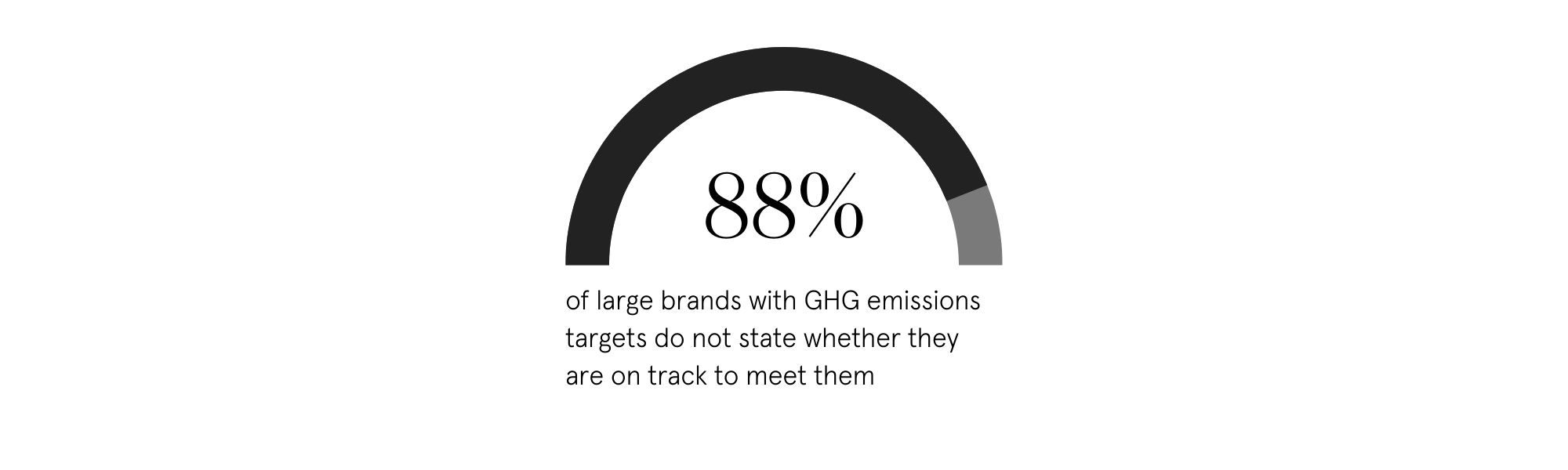

- 87.7% of large brands with greenhouse gas emissions targets do not state whether they are on track to meet them. This underscores the need for governments to mandate reporting on greenhouse gas emissions.

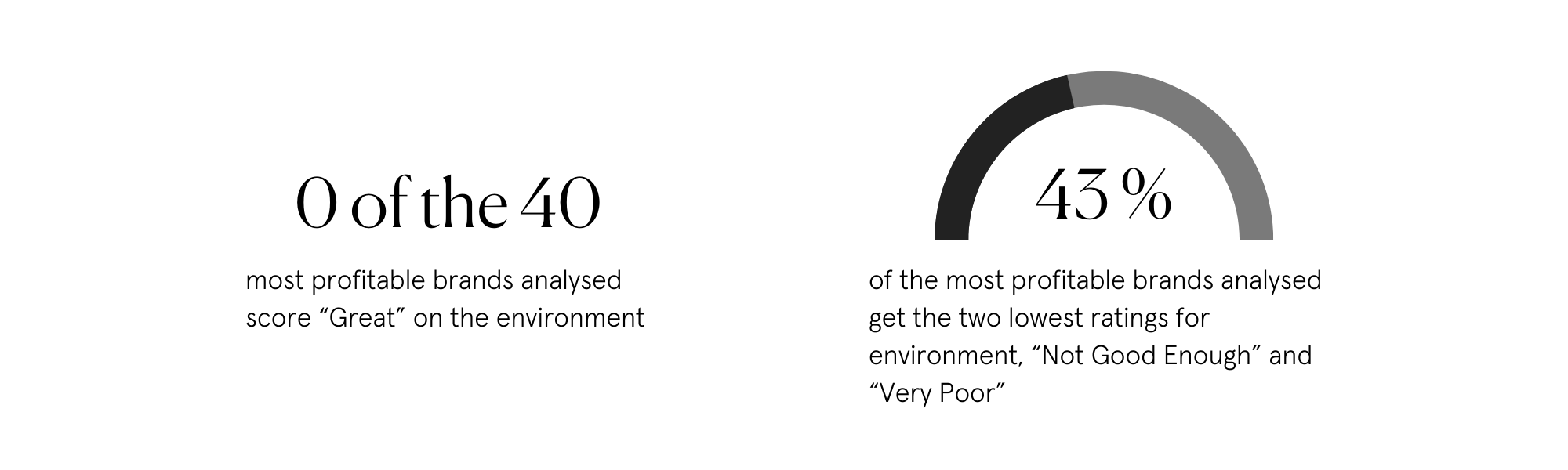

- 0 of the 40 most profitable brands analysed receive Good On You’s top rating—“Great”—for the environment. This means these brands are not demonstrating leadership in environmental policies, transparency, or managing material issues across their supply chains.

- 43% of the most profitable brands analysed get the two lowest ratings for environment, “Not Good Enough” and “Very Poor”—meaning these brands publish little or no concrete information about their sustainability practices and are not adequately managing their impacts across their supply chains. In some cases, these brands may make ambiguous claims that are unlikely to have a material impact.

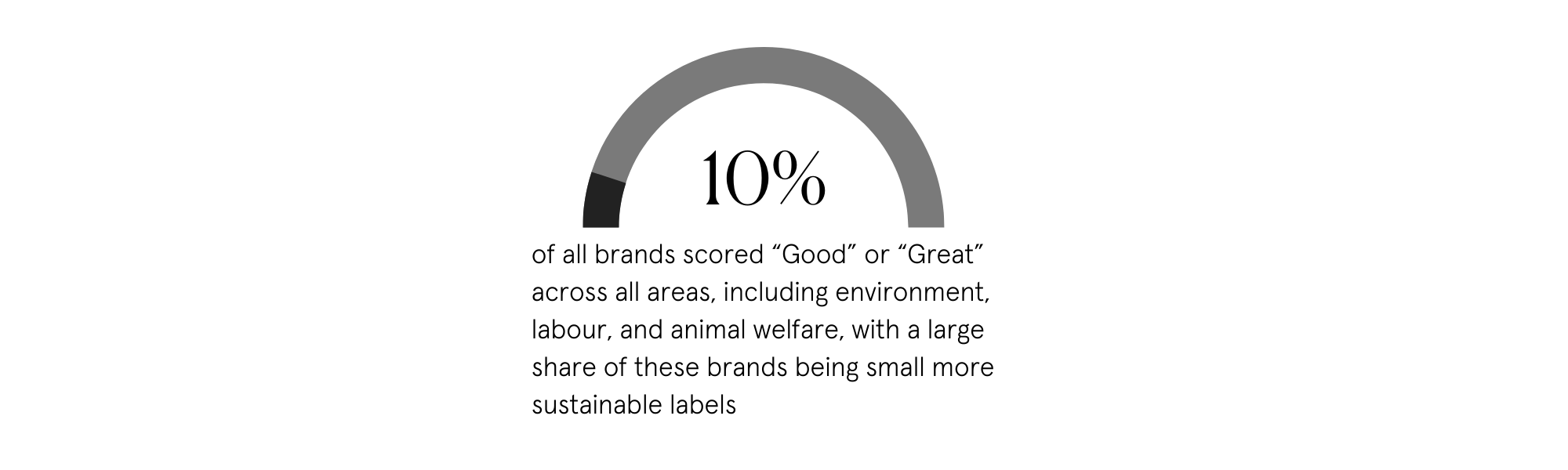

- Only 9.6% of all brands scored “Good” or “Great” across all areas (environment, labour, and animal welfare), demonstrating how the industry needs to do much better. This percentage includes a large share of small and independent labels showing leadership.

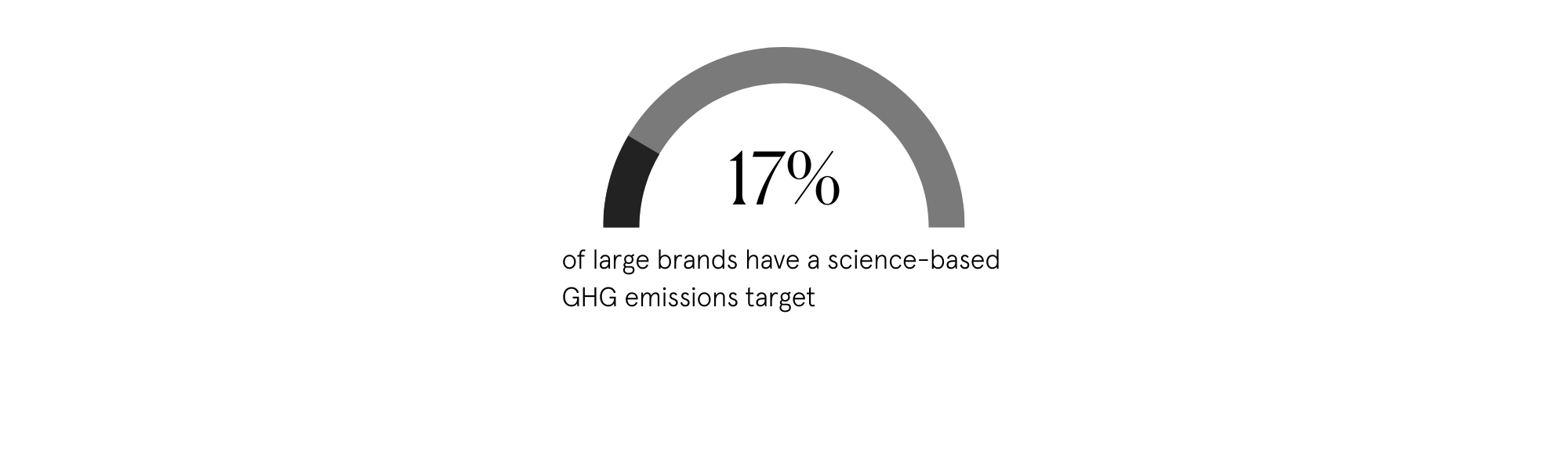

- 16.6% of large brands have a science-based greenhouse gas emissions target. Read on to see why this number should be higher.

The view from COP29

In headline after headline, the evidence underlines that the climate crisis many fear to be on the horizon is, in fact, already here. Yet as world leaders gather for COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan—the 29th meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—we continue to hear more greenwashing than see meaningful action. It’s a critical moment for the future, made all the more acute by the outcome of the recent US elections, with the winner infamously labelling climate change a “hoax” despite the science…

At last year’s COP in Dubai, the first ever global stocktake of progress made towards limiting global warming demonstrated that efforts have been “insufficient“. The world is way off track and may veer off even more in the years ahead if the US reverses all current efforts. Even with the full implementation of all plans, we are still heading towards between 2.1 – 2.8°C of warming, according to the stocktake outline and potentially 2.6 – 3.1°C of warming according to the UNEP’s 2024 emissions gap report. That means more intense heat, more floods, more disasters.

Like all before it, COP29 will aim to avoid that fate and this time the focus is climate finance. Though discussions will likely be highly technical the underlying concept is simple: we need climate action to make financial sense because right now destroying the environment is very profitable.

Right now destroying the environment is very profitable.

The fashion industry exemplifies this unwelcome truth. That’s why it’s also important that we have a handle on what impact the fashion industry is having and where it’s going. But since there’s nothing quite like COP for fashion brands—no mandated progress disclosure—it’s difficult to track. That’s where Good On You’s comprehensive data on fashion brands comes into play. Having rated thousands of brands on these issues, Good On You has data that can give us a sense of the industry’s report card on environmental policies.

New data shows fashion’s climate inaction

In 2021, Good On You kickstarted a first-of-its-kind data project to get a sense of how the fashion industry is working to address its impacts on the planet. The resulting report offered the deepest look yet at the actions brands of all sizes are and aren’t taking.

Now on the cusp of COP29, Good On You reviewed the latest data on 5,821 brands. There are some positive steps forward, but the overwhelming narrative remains rather bleak.

As the cost-of-living crisis made unethically cheap clothes more appealing and microtrends continued to come and go at lightning speed, Shein’s UK sales leapt 40% to £1.5 billion in 2024. The brand is also set to sell shares on the London Stock Exchange in the near future, reaching a potential valuation of over $65 billion. This is despite a storied history of labour scandals and those spiralling emissions.

The ultra-fast fashion model is now so dominant that the preceding generation of fast fashion brands, which were just a few years ago considered the pinnacle—or rock bottom, depending on your viewpoint—of disposable trends are struggling to compete. Amazon has responded with a plan to launch its own discount fashion storefront, allowing Chinese sellers to ship direct to US consumers to compete with Shein and Temu.

It’s a disturbing indictment of an industry that just a few short years ago painted a near-unanimous picture of innovation and dedication to sustainable change. In reality, brands are going in the opposite direction, abandoning targets, and doing little to seriously address their growing emissions. While the bird’s eye view is alarming, there are glimmers of hope. In June, for instance, Berlin Fashion Week, an incubator for many innovative, independent brands, announced it will join Copenhagen Fashion Week in introducing sustainability requirements for any brands showing from 2026 onwards. Such progress is vital but unsurprisingly, much of the major progress is coming from smaller brands and alternative circular, regenerative business models. For meaningful change, we need major brands, which are responsible for the lion’s share of the industry’s emissions, to shoulder much more responsibility.

Context: fashion’s responsibility to act

As part of the 2015 Paris Agreement, governments were asked to create action plans. But it was up to them to decide what action to take, and they missed the mark significantly. The title for the latest Emissions Gap Report 2024, which came out in October, says it all: “No more hot air… please!”

“Some parts of the world are burning. Some parts are drowning and people everywhere are struggling to cope and in many cases to survive—particularly and always the poorest and most vulnerable,” Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN Environment Programme said in a statement around the report’s launch. “The consequences for people, societies and economies of such extreme warming are unthinkable… ambition must be accompanied by rapid delivery, or the Paris Agreement target of holding global warming to 1.5°C by 2100 will be dead within a few years and the target of well below 2°C will take its place in the intensive care unit.”

The scorecard for businesses, which the UN calls “non-state actors”, is probably equally as poor. Reliable, peer-reviewed figures are often hard to come by. That’s especially true in fashion due to the supply chain’s inherent complexity. But as an industry that spans the globe, with single garments often traversing between countless countries including China, the US, the UK, Vietnam, India, Ghana, and Bangladesh within their lifecycle, fashion’s impacts are not trivial.

The UN estimates that the multi-trillion-dollar industry is responsible for 8-10% of the world’s GHG emissions. While other estimates vary, the point remains the same: fashion’s impact is far from trivial. As an industry predicated on growth, that figure could well increase if left unchecked. And in a world scrambling to limit emissions, the story this data tells about large brands expanding production and no reporting progress on their goals is a dangerous one.

But greenwashing remains far too rampant

The average fashion consumer could be forgiven for thinking their favourite brands have responded robustly to climate concerns. From environmental mission statements to promises of cutting emissions and eliminating waste, the fashion industry outwardly seems to have transformed into a custodian of our collective future. “Fashion made from waste and grapes? Welcome to the future”, says one high street behemoth. “We’re facing up the future, doing more for our clothes, our suppliers, our communities, and our impact on the environment,” promises another brand.

It appears that every fashion brand is doing its very best, setting targets such as “we’ll achieve net zero across our value chain by 2030”, and “[our goal is to] be climate positive by 2040”. However, beyond the snappy promises lies a very different reality.

That’s what’s often considered greenwashing—the unjustified and misleading claims from fashion brands that their products are more environmentally friendly than they really are. This manifests in various ways. Sometimes it’s outright deception. Sometimes it’s more subtle advertising. Often, it’s brands making ambitious claims without being transparent around their actual impacts.

Beyond avoiding those misleading claims, the most effective response to greenwashing is for brands to be fully transparent about their impact and how they’re addressing the key issues in their supply chains. That’s why this report goes beyond the greenwashed claims and focuses on data about what brands are really doing.

Most brands we rated aren’t doing enough

Most fashion brands get low scores for their environmental policies, according to Good On You’s rigorous and independent brand ratings. To rate brands, Good On You looks past each brand’s claims and analyses its actions across more than 100 key sustainability issues. Good On You considers a variety of indicators of environmental impact and progress. These include emissions reduction activities, target setting, and the measurement of scope one, two, and three GHG emissions (this means not only counting emissions from brand-controlled sources like offices and warehouses but all indirect emissions like those from energy use, purchased products, and even employee commuting). The environmental ratings also factor in resource management, chemical use, and water use.

Each brand is labelled on a scale of 1 (“We Avoid”) to 5 (“Great”), with brands on the upper end of that scale representing the leaders for their policies. You can find out more about how Good On You’s ratings work here.

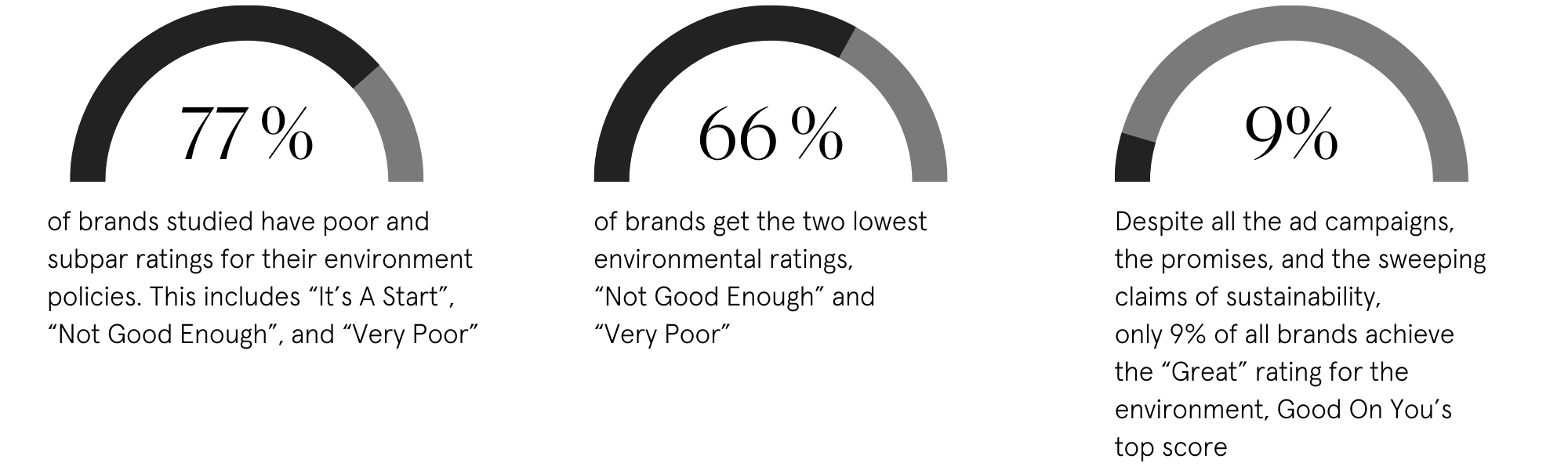

For this report, Good On You analysed 5,821 brands, which have our most up to date ratings. It’s important to note that this is not a random sample of fashion brands. Among them are many major fashion houses, high street shops, and a significant selection of smaller, more sustainable labels. The sample includes a disproportionate share of sustainable brands, meaning these stats are even rosier than the reality (percentages rounded to the nearest whole number):

Smaller brands are scoring better for the planet

Smaller sustainable brands are leading the charge for progress compared with large brands, which Good On You defines based on annual turnover. Their efforts boost the results and make Good On You’s industry-wide data look more impressive than it really is.

If we remove the more sustainable brands from the mix, you’re looking at a much bleaker picture. In other words, the sustainable brands in this sample demonstrate it’s possible to do much better.

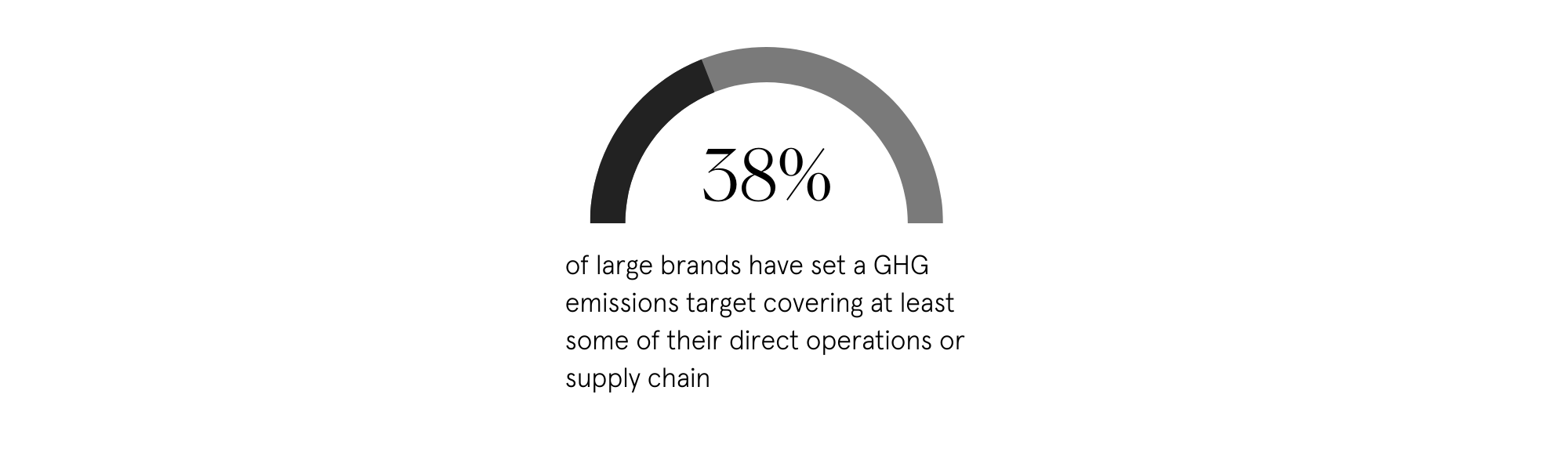

Not all climate targets are up to snuff

The big brands are setting bold targets, but a little digging reveals the targets are not all they’re made out to be. As we’ve seen, brands are rushing to set impressive-sounding targets to show their customers how concerned they are about the climate.

Not even half. And some targets mean more than others.

It’s that “science-based” bit that really matters. Kristian Hardiman, Head of Ratings at Good On You, explains that the “base year” brands choose can make a huge difference. “When I first started working in climate change, loads of brands were setting 2007—the year before the global financial crisis—as their base year. Emissions were quite high and then they dropped, so if they set a target of a 30% reduction compared to 2007, they were already there, they didn’t really have to do much,” he says, adding that he expects 2019, the year before COVID, to become the next base year.

As we’ve previously reported, science-based targets help to avoid that kind of sneaky carbon accounting by ensuring that targets are set in line with the internationally agreed 2 or 1.5 degree warming limit. “The Science Based Target initiative has really done the work of what it would mean for a company to align themselves with the Paris Agreement framework,” explains Maxine Bédat, author of Unraveled and Director of the New Standard Institute. “It’s a way to draw a line in the sand between corporate greenwashing and real action.” But brands must support their entire supply chain in working towards those targets or more will continue to fall short.

The most profitable aren’t leading the way

The most profitable fashion brands are getting the lowest scores for their environmental policies. Some pin hopes for the future on the largest companies with the thickest wallets to fund and drive solutions. But Good On You’s data suggests they’re simply not putting in the work.

For this report, Good On You looked at the ratings for the most profitable brands listed on FashionUnited’s annual index, considered by many to be the benchmarks of profitability across private and public brands. Of the top 40 brands analysed, the numbers paint a picture of the most powerful brands doing the very least.

“I would say that climate change is the area where brands greenwash or try to deceive consumers the most,” says Hardiman. That can be successful because consumers aren’t supply chain or carbon emissions experts.

“We can’t just rely on consumers because consumers can’t be deeply educated in all of these things. That’s way too much of an expectation to put on regular people,” says Bédat. “And so, what we’re seeing is tightening legislation.”

Large brands not transparent about progress

On a consumer level, greenwashing erodes trust. On an environmental level, this lack of meaningful action further derails the path toward achieving the 1.5 degree limit. As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said in the final part of its sixth assessment released in March 2023, “there is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.”

Nations are expected to revise and report on their actions every five years and yet:

Analysis: make unsustainable against the law

If this report tells us anything, the lack of transparency from large brands is a clear sign it’s time governments pass laws that mandate environmental reporting alongside prohibiting misleading claims.

In 2024, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) issued a tailored greenwashing guide for fashion brands and sent letters to 17 well-known fashion brands advising them to review their practices. The CMA said the letters “highlight areas of concern regarding their green claims, such as broad or general terms and whether certain products are being wrongly included in ‘eco’ ranges.”

And in late 2023, the EU reached a provisional agreement on new rules to ban misleading advertisements and provide customers with better product information. Generic environmental claims such as “environmentally friendly” and “eco” will be banned “without proof of recognised excellent environmental performance relevant to the claim.” This push for honesty in sustainability marketing goes hand in hand with its updated Ecodesign Directive which establishes frameworks for making products more durable, reliable, reusable, upgradable, repairable, recyclable and easier to maintain. Also among the Ecodesign Directive requirements is a Digital Product Passport, a concept that would allow environmental information such as product provenance and options for repair to be easily accessed by scanning a QR code or a chip.

These are clear signs it's time governments pass laws that mandate environmental reporting.

The European push for transparency is echoed globally in other policy and legislation proposals such as the New York Fashion Act, which calls for fashion retailers and manufacturers that do business in New York and have global revenues exceeding $100 million to disclose, among other things, supply chain details, environmental due diligence policies, the annual volume of materials produced, and impact reduction targets (which they would be required to meet and report compliance on annually). If passed, these proposed laws and regulations could mean brands face up against fines, sanctions, denial of government aid, and the embarrassment of having to make public retractions and corrections when they’re found in violation.

Challenges in sustainability communications

Despite a crackdown on greenwashing, it’s not resigned to the past. Ostensibly earth-friendly claims still draw consumers and there are cynical forces at play. But fashion academic and strategist Frederica Brooksworth says a lack of sustainability knowledge is also to blame where the professionals communicating these messages are concerned.

Marketers are entering a seemingly creative profession and then tasked with relaying highly complex, scientific information in an accessible way. “I’ve been pushing for law to be taught on fashion programmes and I’ve run my own courses for three years,” she says. “We have a responsibility as educators to really enforce this within the curriculum. If you’re teaching fashion marketing, you need to look at it in terms of consumer protection.

An emerging response to consumer and legal allegations of greenwashing is brands turning on their heels and being brutally honest about their shortcomings. Ganni decided to tell the world “Why we’re not a sustainable brand”, perhaps borrowing from Noah’s 2018 missive along the same lines, while Ace & Tate said, “Look, we f*cked up”, and listed five “bad moves” it had made as a brand, including setting an unrealistic carbon goal. Taking this a step further, some brands are now simply saying nothing at all, a practice that’s been called “greenhushing”. This is to avoid scrutiny on green claims made, but scrutiny is exactly what’s needed for consumers and regulators to ensure action is meaningful and aligned with wider industry and global targets.

Technically, yes, these brands aren’t pretending to be greener than they are, but they are carving a path of least resistance, digging out leeway to do less, aim a little lower. “It’s fine, work on it, but just don’t make it your main message, because then it’s not authentic,” says Brooksworth.

Conclusion: at a critical tipping point

We’re at a critical tipping point for our future, and the pervasiveness of greenwashing—despite overdue regulatory scrutiny—means we simply do not know whether brands are acting on their own self-promoted plans. Updates and ambition are a key metric for COP28 and indeed a habitable climate in future, yet fashion brands who play a key role in protecting that future are obfuscating reality. Some major brands are being more transparent than they were a few years ago. We need to accelerate this change.

With the window of opportunity closing, transparency seems like the bare minimum. “Saying that you can’t operate unless you are operating within the bounds of the planet,” Bédat says, “it seems eminently reasonable, doesn’t it?”