Worried about fashion’s impact on the climate emergency? Then you need to know about the Science Based Targets Initiative. In an unregulated industry, it represents the current standard for greenhouse gas emissions targets.

What are science based targets?

If you’re the sort of person who scours brands’ websites for environmental commitments or reads annual sustainability reports, there’s a good chance you’ve come across the term science based targets (SBTs) lately. While “science based” sounds great—science!—you might have some questions.

It’s understandable if you’re a little sceptical about sustainability buzzwords these days. And on first glance, SBTs may seem like one more addition to fashion’s alphabet soup of sustainability jargon and buzzwords.

Are SBTs really that different from the vague targets brands often set? Let’s investigate.

The Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi), which defines and facilitates SBTs, describes them as providing “companies with a clearly-defined path to reduce emissions in line with the Paris Agreement goals.” It’s a description that answers some questions but poses many more.

Answering those questions might help us, as consumers and citizens, hold brands to their commitments and inform our climate activism. That’s a good reason to dig into the specifics.

Paris: fashion capital, climate capital

Understanding SBTs starts with understanding the Paris Agreement. The legally binding agreement was adopted at COP21 in Paris in 2015. It sets a goal of limiting global warming to “well below 2, preferably 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels”. (“Pre-industrial” is a loosely defined term that bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, class as around 1850-1900).

The agreement came into effect when at least 55 countries representing 55% of global emissions had joined, and the goal was to achieve a “climate neutral world by mid-century”. It was up to different countries to decide how they would work towards the goal, but it could include a host of actions and measures such as investing in renewable energy, taxing polluters, and improving “green” public transport.

Because of Paris’ symbolic meaning in both the climate justice movement and within fashion, protestors have increasingly staged demonstrations at fashion week events—including the famous scene of an activist crashing a runway in 2021—to make statements about fashion’s impact on the planet. This highlights the increasing concern many people have regarding the fashion industry’s links to climate change and the inaction from the biggest brands.

Protester disrupting tonight’s Louis Vuitton show pic.twitter.com/hP8dry4kkz

— jessica testa (@jtes) October 5, 2021

What do science based targets have to do with fashion?

A global goal needs global collaboration, and if private companies like fashion brands decide to carry on as normal, they derail other efforts.

To create the clothes we wear, the fashion industry consistently engages in actions that have an adverse effect on our environment. Shipping, farming, plastic production, coal-fuelled factories, livestock, logging, synthetic textile production, dyeing, mining, and landfilling all sit within fashion’s remit, each with its own impact.

To limit warming to 1.5 degrees, the fashion industry needs to reduce its GHG emissions.

Such resource use, production, and waste take their toll. And there are many estimates about what the industry’s impact is. Consulting firm McKinsey estimated that the fashion industry was responsible for 2.1 billion metric tonnes of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2018. That’s 4% of the global total and the equivalent to the emissions of France, Germany, and the UK combined. The UN has previously estimated that fashion is responsible for 8-10% of GHG emissions. Whatever the precise number, it’s a significant one.

To limit warming to 1.5 degrees, the fashion industry needs to reduce its GHG emissions. But how do brands know they’re reducing them enough to keep us within that safe level? And how do we know that brands are making meaningful environmental promises? That’s where SBTs come in.

How are science based targets different?

There are tonnes of sustainability targets flying around, you can’t miss them, and they’re often fodder for greenwashing: internally set, unverified, and vague. Are SBTs different?

For a target to be considered science based it must be in line with the goal of limiting warming to well below 2 degrees, with efforts shown to limit it to 1.5. A brand must register with the SBTi, develop a target, and then submit it so the SBTi can validate whether it is in fact science based.

SBTi represents the “current gold standard” in this space, says Kristian Hardiman, Good On You’s head of ratings. It’s because of this specificity, scientific grounding, and validation that Good On You rewards a “higher proportion of points to brands setting SBTs when analysing GHG emissions,” Hardiman says of Good On You’s brand rating methodology.

Many activists, academics, organisers, and researchers agree that SBTs represent the best standard we currently have. It’s what all brands should be targeting, regardless of their size.

“It’s really important that we try to align all business—and life in general on our planet—with the 1.5 degree pathway,” says Rebecca Coughlan, transparency manager at non-profit advocacy organisation Remake.

Why? Because according to an alarming IPCC report released in February 2022, “any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all”.

IPCC followed this with a report in April 2022 that The Guardian described as “what is in effect their final warning”. The co-chair of the working group behind the report is quoted as saying “it’s now or never, if we want to limit global warming to 1.5C. Without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, it will be impossible.”

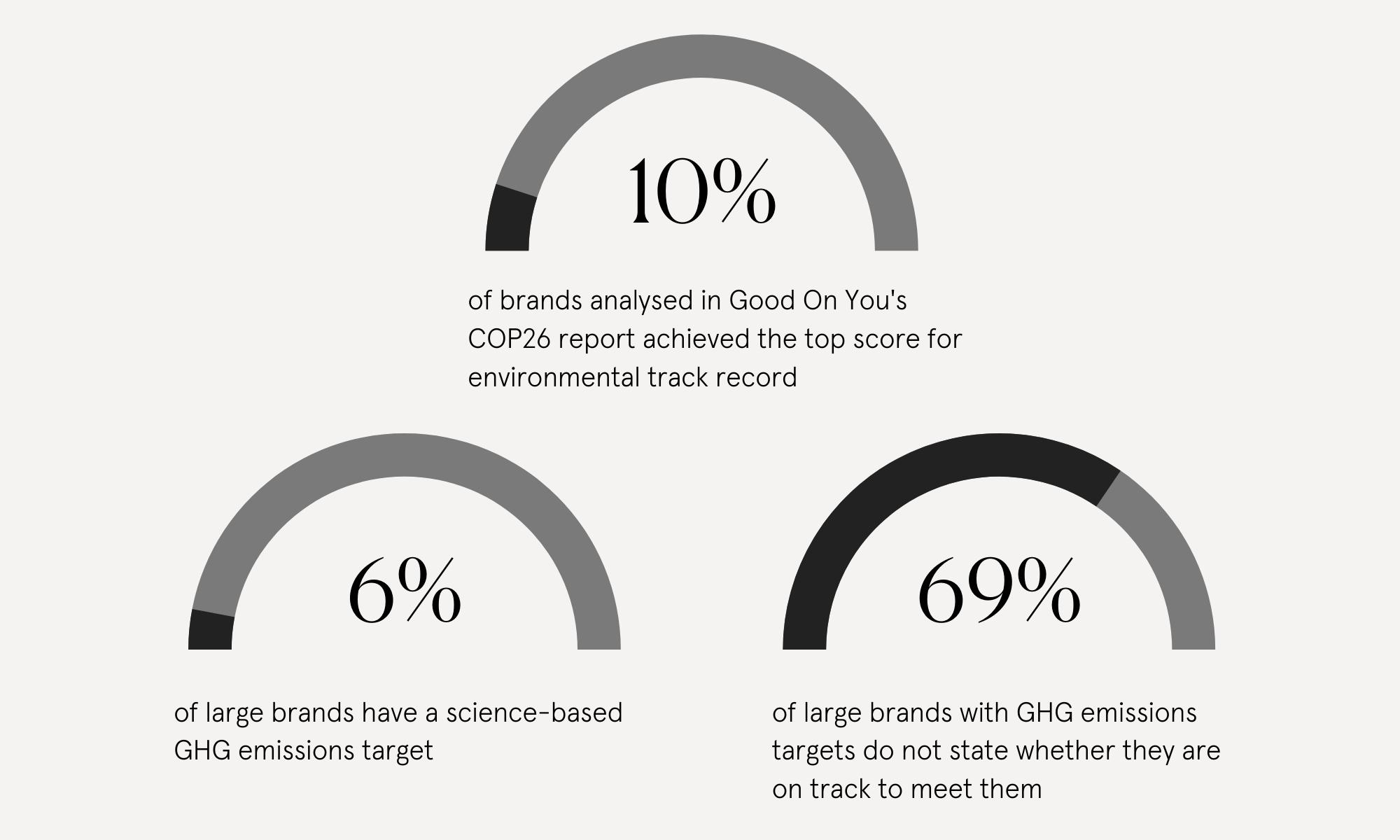

Unfortunately, fashion brands are not doing enough. Around COP26, I worked with Good On You analysts to produce this deep-dive survey on what actions brands are taking for the climate. Based on newly released data on 2,500 brands’ environmental track records, the report found that brands aren’t doing enough to address their impacts on the climate emergency. For example, only 10% of brands analysed earned Good On You’s top score for the environment. And where the biggest and wealthiest brands have GHG targets, 69% of them are not disclosing whether they are even on track to meet them.

This all imbues the conversation about SBTs with a heightened sense of urgency. “SBTs show companies how much they need to reduce [their emissions] by and give them a good timeline to be able to align with that pathway so we can hopefully avoid the worst effects of climate change,” says Coughlan. At the very least, that’s where brands need to start if the fashion industry is to mitigate its role in the climate emergency.

How can brands reduce their emissions?

Allbirds—a footwear brand currently scoring “It’s a Start” in Good On You’s rating system—made 10 commitments when introducing its SBT “Flight Plan” in 2021, says Hana Kajimura, head of sustainability. (There are a variety of factors that explain Allbird’s score beyond its GHG targets.)

These commitments include 100% of wool coming from regenerative sources, sourcing 100% renewable energy for facilities that are owned and operated by the brand, reducing the use of raw materials by 25%, and doubling the lifetime of footwear and apparel products. Each commitment is to be achieved by 2025 to help accelerate a longer-term target to be as close to zero emissions as possible by 2030.

Other emissions-reducing activities that brands can undertake include things like moving away from fabrics derived from fossil fuels, installing solar panels on factory rooftops, producing fewer products, and reselling existing products.

What are scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions?

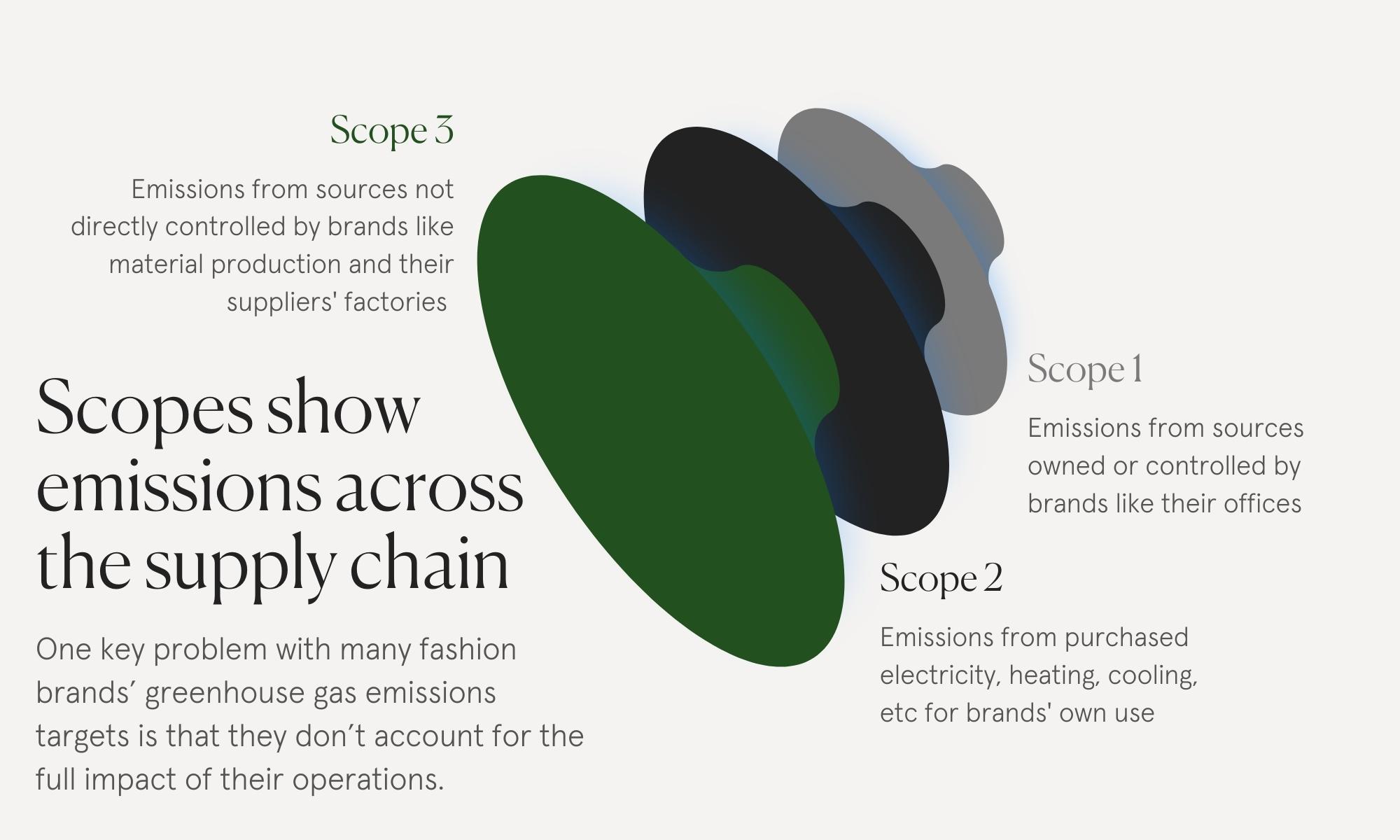

One key problem with many fashion brands’ targets is that they don’t account for the full impact of the supply chain. Often, brands might focus on reducing emissions in one area of their operation, which can verge into greenwashing territory if they’re only focused on the parts of their operations that already have the least impact.

This is where it’s helpful to understand what scopes mean. “Scopes are a way to delineate between direct and indirect emissions,” Hardiman explains. In other words, it’s about how a company goes about accounting for its greenhouse gas impacts. “You calculate your emissions and then within each scope, you determine the best way to reduce emissions.”

There are three types of scopes. And while they cover the complexity of the supply chain, their definitions are quite straightforward: scope 1 emissions come from sources owned or controlled by the brand—think retail shops and corporate headquarters. Scope 2 emissions come from purchased electricity, steam, heating, and cooling, for a brand’s own use. And scope 3 emissions come from other sources that are not technically controlled by a brand such as transportation, extraction of materials, non-owned supplier factories, employee travel, and the use of products that have already been sold.

When it comes to where the biggest impacts lie, it’s different scopes for different industries. “For most fashion companies, scope 3 is usually huge whilst scope 1 and scope 2 are relatively small,” Hardiman says. “But for some companies outside fashion, such as airlines, their scope 1—their direct operation—will be enormous.”

Absolute v intensity targets—what’s the gist?

Along with the different scopes, there are different types of reduction targets, too: absolute and intensity. With absolute reduction targets, brands are targeting an overall reduction of emissions compared to a certain point in time. So, a brand may say, “We’ll reduce our emissions by 35% by 2035 compared to 2005 levels”. An intensity reduction is when a brand targets reducing emissions per unit. And intensity targets can be both physical (ie per garment made) or economic (ie in relation to profit).

Where does the SBTi stand on these details? Although, as Coughlin notes, scope 3 is where the majority of fashion’s impact lies, the SBTi only requires scope 3 targets if the associated emissions are “40% or more of total scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions”.

In terms of reductions, brands can choose between absolute and intensity reduction targets. However, it is worth noting that there are currently no approved examples of physical intensity targets, ie a brand saying it will reduce emissions by 20% per garment made.

Better targets aren’t a substitute for regulation

Of course, not all experts agree with the current framework set out for SBTs, such as allowing intensity reductions. “[Physical intensity reductions are] hugely problematic because the climate doesn’t care if you have more efficient production if you increase volumes overall,” says Nusa Urbancic, campaigns director at Changing Markets Foundation, which recently launched a campaign against greenwashing in fashion.

Ultimately, this all points to the urgent need for legislation—for governments to mandate the actions the industry won’t take on its own.

“[The SBTi] needs to strengthen transparency, how much it covers supply chain emissions, and what’s in scope,” says Urbancic. “They also need to do really rigorous reporting every year or two years on where these companies are with regards to achieving their targets. It’s currently enough for brands to say, ‘oh sorry, we didn’t manage it’. So, then what? Nothing. There are no consequences.”

Ultimately, this all points to the urgent need for legislation—for governments to mandate the actions the industry won’t take on its own. Most experts agree that it’s long overdue for governments to step in and mandate things like greenhouse gas emissions reporting. And most experts agree that we need regulation to achieve the kind of systems-level change that needs to happen to address the fashion industry’s impacts.

The pros in an unregulated industry

Today, in an unregulated industry that largely plays by its own rules, SBTs provide brands with a firm roadmap for “how much and how quickly they need to reduce their GHG emissions”. Verified and climate-focused, SBTs are focused on creating a safe, liveable future while other targets may sound impressive but could have little to no impact overall.

A late 2021 report by Good On You found that only 6% of large brands have science based GHG emissions targets. But if SBTs become an industry standard, we could see a shift towards more meaningful, measured climate action.

There are undoubtedly many areas for improvement regarding reporting, incentives, and penalties but perhaps Kajimura puts it best: “Given the current trajectory, we simply don’t have time to wait for perfect solutions. Instead, we have an opportunity to innovate.”