Our editors curate highly rated brands that are first assessed by our rigorous ratings system. Buying through our links may earn us a commission—supporting the work we do. Learn more.

Can the use of animal products in fashion harm the environment in the same way that the meat industry does? And if so, what alternatives are out there?

How animal products in clothing are harming the environment

In recent years, we’ve become increasingly aware that the choice of whether—or how often—to eat animal products can have a huge impact on our environmental footprint. In fact, The Guardian reported on a study that showed “vegan diets resulted in 75% less climate-heating emissions, water pollution and land use than diets in which more than 100g of meat a day was eaten. Vegan diets also cut the destruction of wildlife by 66% and water use by 54%.”

But what about our choices regarding what we wear? With billions of animals used or reared to source materials every year, can the use of animal products in fashion harm the environment like the meat industry does? And if so, what alternatives are out there?

Whatever your diet, it’s well worth considering how animal rights in the fashion industry can be linked with broader environmental issues.

Is animal welfare in fashion getting better?

Back in 2023 international animal welfare organisation FOUR PAWS used Good On You’s brand rating data to inform its Animal Welfare in Fashion report, which aimed to identify where industry efforts could be prioritised to maximise impact for animals on the ground, while supporting the industry’s sustainability objectives. To get a clear view of how the industry is doing for animals, Good On You rated 100 fashion brands from 15 countries across nine market segments, including luxury, sports, and fast fashion.

We found that the fashion industry could be on the cusp of a significant transformation, driven by a growing awareness of its environmental and ethical impact. There were some signs of progress, with 17% of the brands selected in 2023 having improved their Good On You rating for their impact on animals since 2021. The report also found that more brands have engaged and made progress in improving animal welfare, especially in the use of certified wool and down, and the adoption of fur-free policies. But, overall, most brands still caused too much harm to animals throughout the supply chain: only 15% of the rated brands achieved Good On You’s top ratings of “Good” or “Great” for animals, and 18% of brands still used wild animal materials (including fur, exotic skins, and decorative feathers).

In 2026, though, things continue to shift—several prominent Fashion Weeks have banned fur including New York, Copenhagen, and London; as have all major fashion media publishers (think Condé Nast and Hearst); and most recently, Rick Owens committed to removing fur from its designs after campaigners protested outside stores around the world.

Wool and cashmere

What could be cosier and more comforting than a woollen sweater? Unfortunately, the facts about wool production’s impacts are not so reassuring, not least the fact that more than 1.2 billion sheep are farmed for wool worldwide.

One of the main issues with wool—similar to the problem that makes livestock use for food so damaging—is the large amount of methane produced by sheep, and cattle in general. Methane is a greenhouse gas 80 times more potent than CO2 in the short term. And the percentage of global greenhouse gas emissions that comes from livestock is pretty big. As with many attempts to quantify emissions, the estimates can vary, but research suggests they make up 12-19% of all global emissions. And Vox reports that: “According to one analysis of wool production in Australia, by far the world’s top exporter, the wool required to make one knit sweater is responsible for 27 times more greenhouse gases than a comparable Australian cotton sweater, and requires 247 times more land.”

Nearly 80% of all agricultural land worldwide is used for pasture and arable land to grow feed for farmed animals, including sheep. Grazing occupies 26% of the earth’s ice-free surface. When we clear land for pasture, it results in biodiversity loss, depriving wild animals of their natural habitat and increasing the risk of endangerment and extinction. Additionally, cutting down trees during land clearing releases greenhouse gases. Land degradation and even desertification are some of the additional consequences of intensive sheep farming. In Mongolia for example, the increased demand for cashmere has meant herd sizes have increased, driving the desertification of the grasslands. Though more holistic land management methods for grazing livestock animals are gaining popularity and support, they aren’t yet widely practised.

This doesn’t mean you must go without your snug winter staples. The first step may just involve being mindful of the wool products you own and taking care of them to ensure they last. Buying secondhand wherever possible is another great option. If you do want to buy new clothes made out of wool, look for ones made from recycled wool, wool certified by the Responsible Wool Standard, ZQ Merino Standard, or the Soil Association Organic Standards, bearing in mind that the welfare guarantees for the animals differ across certifications. For more info, read our article that looks at the ethics and sustainability of wool.

Leather

While “real” leather jackets, boots, and handbags were once the height of cool, our awareness of the cruelty behind their production can put a dampener on their attraction. Lots of people think leather is sustainable because it’s simply a by-product of the meat and dairy industries—in other words, that leather reduces waste. However, it’s not true that leather is a mere by-product. As well as animal welfare concerns, there are a whole lot more reasons to consider saying no to leather and making the switch to the diverse range of leather alternatives available.

Environmentally, you’d be hard-pressed to find a worse offender in terms of air, water, soil, and atmosphere pollution. This is because the process of turning animal skin into leather involves many high impact chemicals, dyes, and finishes, and a large amount of energy and water (some estimates suggest that the creation of a cowskin tote bag might require more than 17,000 litres of water, though the statistics vary depending on the source). Finally, effluent from tanneries—a known pollutant of major waterways—contains washed-out chemicals from the production process including sulphur, nitrogen, and ammonia.

Here again, deforestation is a big issue due to cattle ranching and the need to grow feed for the animals. Cattle rearing is a leading driver of habitat destruction in Australia, with similar stories playing out across the globe.

Greenhouse gas emissions are another problem, with Collective Fashion Justice estimating that a pair of cow-hide leather boots, seemingly innocuous shoes, have a climate footprint of 66kg of CO2e—the equivalent of charging 8,417 smartphones.

So, is faux leather the answer? It may avoid animal-derived materials, but animal-free or “vegan leather” can be something of a lucky dip when it comes to environmental footprints. Unfortunately, many leather alternatives contain some kind of plastic—whether bio-based (ie not made from fossil fuels), or petroleum-derived. This means they still cause environmental damage in production and are unlikely to be biodegradable.

Fur

Fur has the dubious honour of being the first garment that people associate with animal cruelty, with famous protests such as the throwing of red paint, and PETA’s “I’d rather go naked than wear fur” campaign etched into popular culture.

The environmental impact of fur in fashion varies depending on the garment and animal used, but in general, many of the problems present in the production of wool and leather (toxic chemical runoffs in the after process, and carbon emissions produced in the course of farming the animals) are also an issue with fur.

What about faux fur? It’s great news for our animal friends, of course. And since animals are not farmed for the material, the related emissions are not directly produced. But there are still major problems to consider when buying faux fur clothing, since it’s usually made from plastic-based synthetic materials like polyurethane (PU) that contribute to microfibre pollution, don’t biodegrade, and require lots of chemicals to produce, just like some faux leather products. As yet, no plant- or bio-based fur alternatives have proven to be commerically viable and largely scalable.

Second-hand fur is available, but some argue that this still perpetuates the idea that it is okay to wear the bodies of our fellow earthlings.

Animal skins and furs can also be a crucial source of income for certain remote Indigenous populations, and can greatly contribute to the growth of their communities. Putting Indigenous practices under the microscope while ignoring cattle farming in the West is inconsistent at best and likely has roots in racist and colonial thinking.

Down

Down feathers are commonly used in clothing items, but since they’re often tucked way inside our clothes, it’s easy to overlook their presence—and impact. Unfortunately, the down industry is as cruel as the fur and leather industries. Not only does down production cause harm to animals, but it also harms the environment.

Although down is biodegradable, it is often used in jackets and coats made of non-biodegradable materials. Even if a puffer jacket is made from recycled polyester—which makes it slightly better than a virgin polyester one—this synthetic material prevents down from properly biodegrading unless the materials are separated from each other and disposed of correctly at the end of the garment’s life.

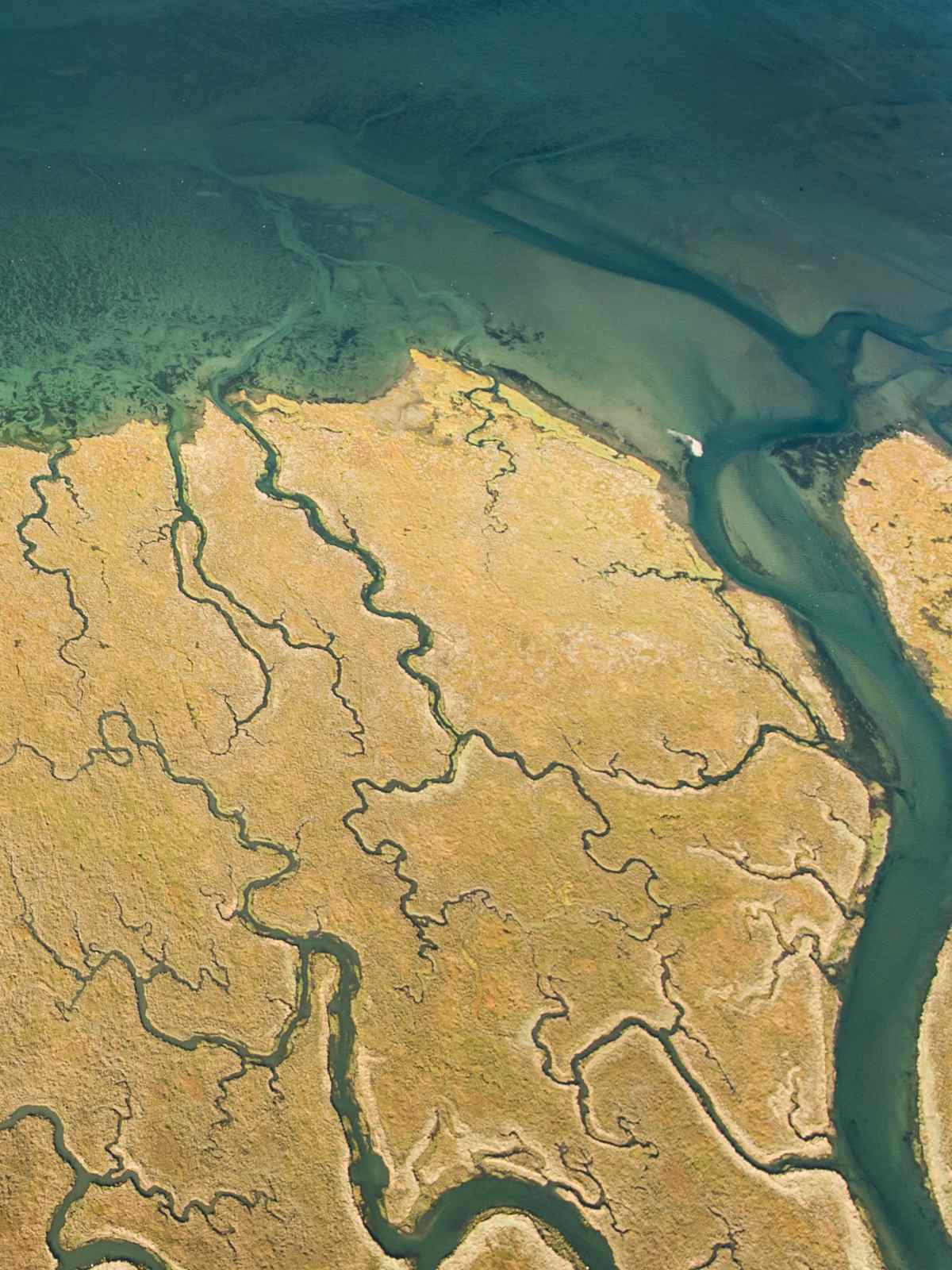

Factory farms housing ducks and geese also have a significant impact on the planet. Runoff from factory farms like those confining ducks and geese is full of phosphorus-rich faeces, which often results in eutrophication. That is a process where a body of water becomes too rich in particular nutrients and dense blue-green algae grows, suffocating everything beneath the water’s surface. This can result in dead zones where aquatic life cannot survive.

Water surrounding slaughterhouses—not just factory farms—is also put at risk by the down industry when ducks and geese are slaughtered in abattoirs that release massive amounts of wastewater. The organic matter in this wastewater is not only bad for the planet but for surrounding (usually lower-socioeconomic) communities, too.

So what are your options? Opt for pre-loved down coats or seek out animal-free alternatives like PrimaLoft P.U.R.E, PrimaLoft Bio, Thermore, or Flowerdown.

Silk

Despite being dubbed a natural fibre, silk’s sustainability can vary depending on how it’s processed and how sericulture (the production of silk) facilities are fuelled.

Silk production is an inefficient process as it requires a significant amount of mulberry leaves to be grown to feed silkworms. It’s estimated that 187kg of mulberry leaves are required to feed enough silkworms to produce just 1kg of raw silk. So many leaves and so much land to grow them on means that the mulberry leaf farm practices tied to silk production contribute a lot to the material’s overall impact.

A note on choosing materials

Of course, no material is perfect in terms of its environmental impact. Materials and fibres in fashion are a complex issue, and through our research, we found there is no established hierarchy of sustainability for materials in the fashion industry, and very limited comparable data (eg Life Cycle Analysis). What is clear is that every single material on the market today has some sort of trade-off and impact on the planet, and a mixture of preferred materials is needed going forward. Above all, we believe that you are the final decision maker when choosing materials for yourself. Figure out what is most important to you and let information, such as the ratings for brands’ impacts on people, planet and animals in our directory, guide your process.