Many are questioning the ethics of thrift flipping, but what could be so bad about giving unwanted clothes a new life? And is the argument against thrift flipping valid?

You might have heard of ‘house flipping’ before—a type of real-estate investment strategy where you buy, renovate, and resell a house for profit. But did you know some people have started flipping clothes?

Yes, ‘thrift flipping’, as it is called, is becoming increasingly popular, in part thanks to TikTok. Users have been posting videos of tutorials explaining how to zhuzh up pre-loved clothes. At the time of writing, the thrift flip hashtag on TikTok has more than 1.8 billion views, and the most popular video has almost 1 million likes.

But many are starting to call out the practice of thrift flipping, blaming it for the gentrification of second hand shops, as well as perpetuating fatphobia.

With so many conflicting opinions, we wanted to take a deeper look at the issue. What are the arguments in the debate surrounding thrift flipping? Is thrift flipping really a problem? And most importantly, what can we do about it all?

What is thrift flipping?

By now, we’ve all read and seen reports repeatedly proving that the fashion industry is hugely wasteful and exploitative. And as more and more people are waking up to this fact, a growing number of shoppers want to make better choices about what goes in their wardrobe.

That’s led to an ever-increasing interest in second hand shopping, which is arguably the most sustainable way to shop. Think about it: Buying pre-owned clothes allows us to add items to our wardrobe without using additional resources in the manufacturing process and keep (some) clothes out of landfills.

Resale platform thredUP predicts online thrifting will grow 69% between 2019 and 2021. Some even believe that the resale sector will be bigger than fast fashion within ten years. But, if you’ve ever been to a second hand shop, you might not find anything that immediately suits your style. And increasingly, fast-fashion garments line the racks at your local charity shops.

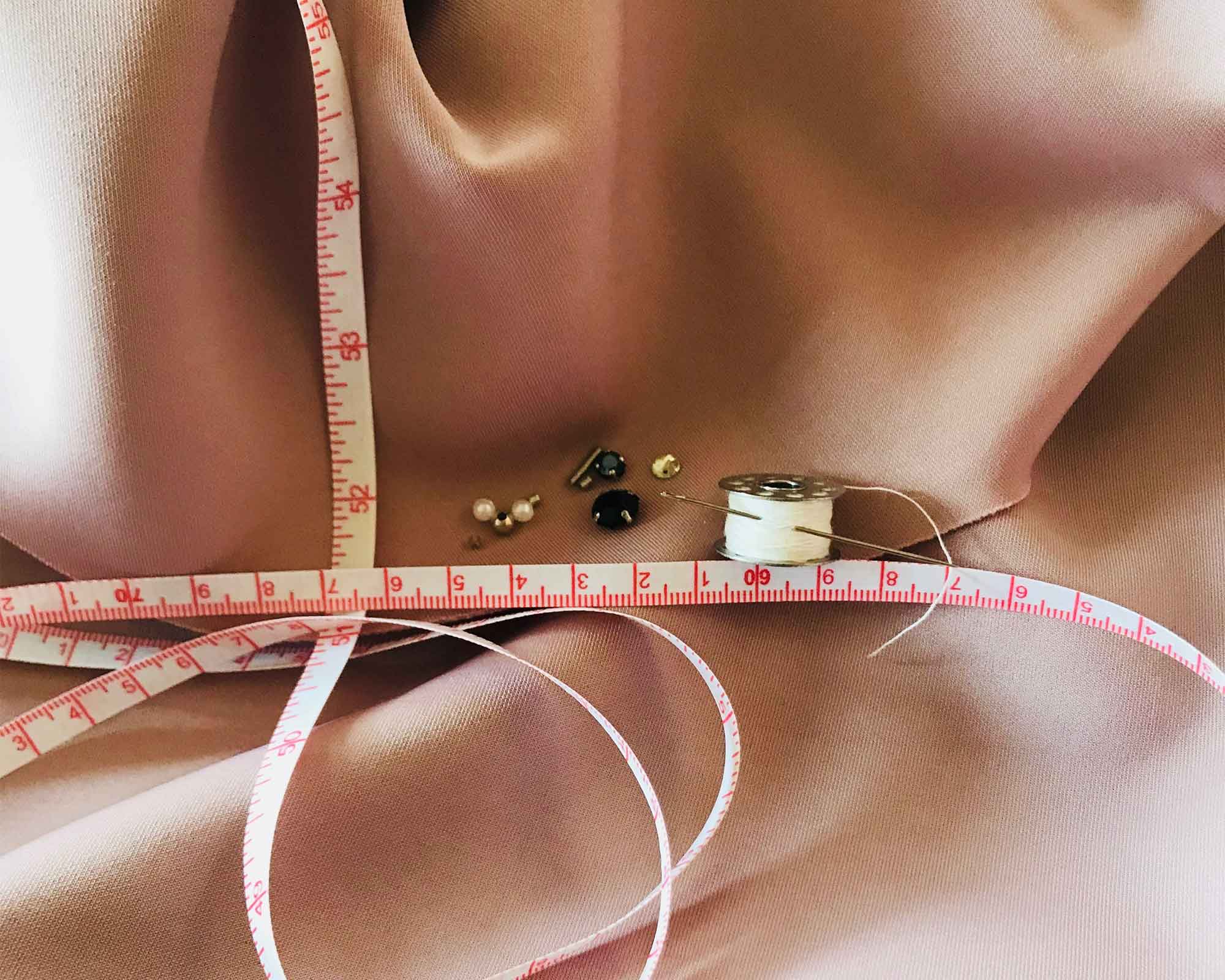

Some people had the idea of upgrading their second hand finds by turning them into something completely new: an oversized shirt becomes a cute two-piece set, hoodies become cropped bustiers, and we’ve even seen jeans turned into a bag.

Thrift flipping is not that new of a concept—it is similar to upcycling, where items are repurposed and used again to ensure we get the most out of the materials.

For many, thrift flipping started as a hobby, something to do during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Some keep these new items for themselves, but some also turned thrift flipping into extra income, going out to thrift stores specifically to find items to flip and resell for a profit. Search on Google, and you’ll find a plethora of articles and guides about how to make an income out of thrift flipping.

Is there a thrift flipping problem?

On paper, thrift flipping seems to be a sustainable solution. What could be so bad about giving unwanted clothes a new life? Lately, though, we’ve seen a lot of headlines questioning the ethics of thrift-flipping and the motivations of those who do it. And is the argument against thrift flipping valid?

The most significant issue you might’ve heard about thrift flipping is that it could be contributing to the gentrification of thrift shops. That’s something people have debated long before the current thrift flipping trend. It’s the phenomenon where affluent shoppers are said to buy second hand as a commodity. At the same time, less affluent shoppers rely on thrifting as a necessity. Some argue that privileged thrift flippers are taking away resources for low-income families when they buy clothes to make a profit rather than to wear. Some also say the practice is leading to a decline in the quality (hello, fast fashion!) and the number of clothes available.

This theory is further reinforced by the increasing popularity of reselling apps like Depop and Vinted, allowing people to make extra cash selling their clothes rather than donating them to their local thrift shop. It has even been argued that the increased demand is driving second hand prices higher, making it even harder for low-income communities to find quality clothes they can afford.

While the issues of gentrification may seem broad in scope, a more specific concern raised by many is the idea that thrift flipping is rooted in fatphobia. This is where we see thin influencers buying plus-size ‘oversized’ second hand items that are already in short supply to transform them into smaller garments.

These concerns are valid, especially considering the scarcity of plus sizes in many thrift stores and fashion’s broader failures with size inclusivity. But the reality is that there’s no scarcity of clothing. It’s quite the opposite. There are just too many clothes on Earth. Two million tons of clothing items are donated to charities every year, more than second hand shops can manage, and they often don’t know what to do with all the donations. It’s hard to believe thrift flippers are creating scarcity and taking away valuable resources, even if the clothes are bought in bulk. And let’s face it, no one’s going to buy a second hand shop’s entire stock. The increase in second hand prices is real. Still, it is just as likely due to inflation—knowing the number of clothes donated each year, it’s unlikely such a small portion of thrift flippers are buying enough to create scarcity and drive the prices dramatically higher.

What really happens to unpurchased thrift store goods is far more alarming: A tiny portion of unsold second hand garments are recycled. The rest ends up in landfills—like 84% of clothing—or shipped abroad to countries like Ghana, which end up inundated with unwanted clothes. It’s good that some people can keep clothes out of landfills by flipping and prolonging the lives of garments while reducing waste and supporting thrift stores.

View this post on Instagram

How to be a more conscious thrifter

With clothing production being the third biggest manufacturing industry and causing 8-10% of carbon emissions, we all need to buy fewer new items and more second hand. Repairing, altering, upcycling, mending, and yes, thrift flipping allows us to be creative, learn new skills, and, more importantly, give discarded fashion leftovers a new lease on life.

That being said, we should listen to the concerns around thrift flipping and acknowledge that there are ways we can be more conscious about how we thrift. Selling second hand clothes that have been flipped isn’t as bad as it has been made out to be, but we also need to recognise the privilege of being able to do that. If you love thrift flipping, why not start with what you already have in your wardrobe (or your mom’s, your dad’s, your grandparents’)?

The issues are complex and have many layers. Still, they shouldn’t stop us from shopping second hand and being mindful about where and what items we buy. For example, you might avoid buying items in low stock or high need, especially if thrifting in low-income neighbourhoods.

The debate surrounding thrift flipping also presents an opportunity to challenge our ideas of fashion as consumption. Second hand fashion is gaining traction among younger generations, and in addition to thrift flipping videos, we are seeing more and more influencers joining the trend, encouraging their followers to thrift via ‘thrift hauls’. This type of content plays on the idea that fashion is disposable and encourages consumption. Yes, buying second hand is often the most sustainable way to shop, but there’s a deeper psychological question we all need to grapple with. And that’s the overconsumption of clothing that our society has accepted as normal. Critically evaluating our individual relationships with buying clothes in whatever form—asking whether we really need something extra in our wardrobes—is a good first step.

The most alarming problem is fast fashion

Should you stop thrifting or shame people who do? No. Should we all be more mindful when shopping, even at thrift shops? Yes. Should you keep examining the more profound issues the fashion industry is facing? Absolutely.

The current state of the fashion industry is unsustainable—it produces too much poor quality clothing that doesn’t last, and it pushes us to consume again and again. It lacks size-inclusivity and diversity—and don’t get us started on the exploitation of people, the planet, and animals. These issues then trickle down to second hand shops.

The poor quality clothes in your local thrift shop aren’t the result of thrift flippers buying all the good items. They’re mostly the fault of the wasteful and exploitative fast fashion industry that values profit above all. The lack of plus size second hand clothes results for the most part from a lack of size inclusivity at the start of the supply chain.

We should be careful when thrifting, but what really needs to happen is a systemic change at the top. We need to move from the throw-away culture, see value in our clothing, and stop producing and buying so much. Conscious thrift flipping has the potential to help us reshape our values.

Let’s push the industry to do better. And let’s come to appreciate the creativity of upcycling. The idea of saving clothes from landfills and giving them a new life is, ultimately, a good thing.