The Awajún people of the Peruvian Amazon rainforest use a traditional technique to collect sap from trees regeneratively. Now, they are working with Caxacori Studio to turn this sap into a bio-leather that supports their community, helps defend against deforestation, and offers the fashion industry an alternative to unethical animal-derived leather. It’s the subject of a new film, SHIRINGA: Fashion Regenerating Amazonia, directed by Emma Håkansson, activist and founding director of Collective Fashion Justice. Here, she meets the community at the heart of this leather alternative.

Regeneration is central to the Awajún community’s leather alternative

“Mother Earth provides us the sun, the water, the shiringa trees and everything else here and a part of nature,” says Doris Pape Petsa. “We live with higher powers: the mountains, the river and the forest. We are grateful for that.”

Petsa lives deep in the Peruvian Amazon rainforest, where she leads and encourages other women to protect their community and forest home by collecting tree sap that is then transformed into bio-leather for fashion.

As I sit and speak with her via two translators—from English to Spanish, then Spanish to her native Awajún language—birds sing and large, striking butterflies I’ve never seen before flutter past and occasionally land on us. The air is warm and heavy with humidity, but you can feel the cooling effect of the giant trees and plants we sit amongst. When we look up at the sky we see whispers of a glistening sun through the dense, emerald canopy some 40 metres above.

I am here directing a film called SHIRINGA: Fashion Regenerating Amazonia, because Petsa and other women, like Rosalia Manuig Taan, are proving that fashion can exist in a way that helps to protect people, our fellow animals and the planet at once.

Taan, who is several decades younger than Petsa, tells me, “If people really understood how fashion can destroy or protect life, we would all live better.” She and Petsa have just shown me how they carve fine, shallow lines into the trunks of shiringa trees that have stood tall over them and their community for hundreds of years.

Their carvings become trickles of white latex sap, and once enough is collected in a small cup, the markings are “healed with soil” and the tree is left to rest. The engravings will disappear, they explain, pointing to a scabbed carving around the other side of the tree and an almost healed one on another.

If people really understood how fashion can destroy or protect life, we would all live better.

Rosalia Manuig Taan – Awajún community member

This is an example of what regenerative fashion can look like. Sap is collected from these trees without causing permanent damage, and it’s used in a formula that is spread over native Peruvian cotton to create a bio-leather. This supply chain also supports Petsa, Taan, and their community to defend against deforestation.

“Not everyone shows care for the Earth like we do,” Taan says in the SHIRINGA film. The Amazon rainforest continues to be decimated by deforestation that is linked not only to enormous emissions and biodiversity destruction, but also wildlife endangerment, and Indigenous land rights violations—usually violent—against the communities who have long protected the nature they live as part of.

The leading cause of deforestation in the Amazon is inherently exploitative cattle ranching, and fashion’s use of leather—a profitable co-product of meat production—fuels this crisis. “The jungle is burnt. The lives of the animals are not respected. Animals are abused while Amazonia’s animals and people lose our homes”, Taan says.

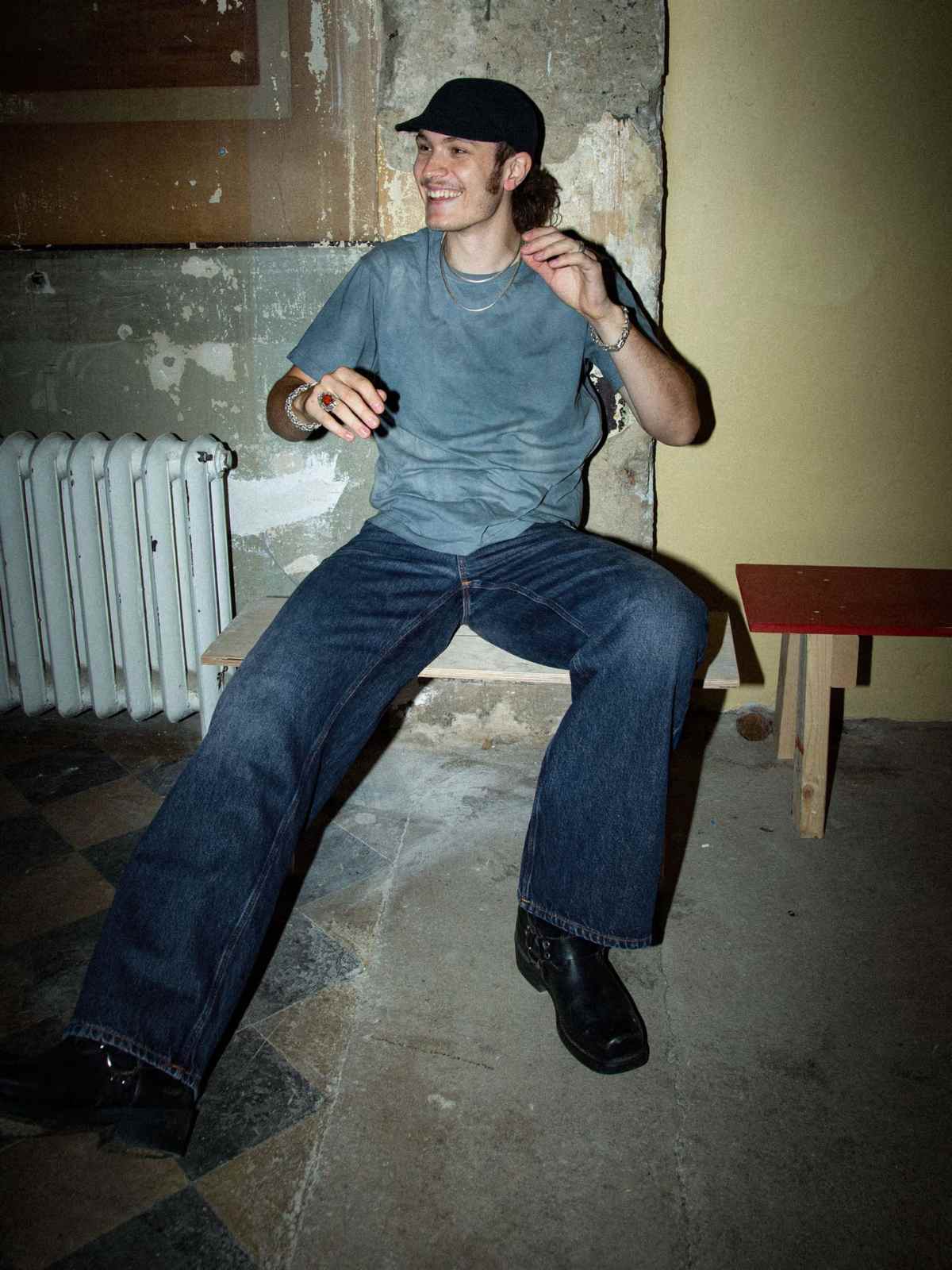

Emma Håkansson with Rosalia Manuig Taan behind the scenes of SHIRINGA: Fashion Regenerating Amazonia.

How shiringa bio-leather benefits the Indigenous community

Taan and her community of Awajún people (there is more than one) live in an area that has been given reservation status by the Peruvian Government, protecting it from this deforestation. “Our land was once in danger of being cut down for profit, but we keep it safe and alive,” she says.

On the border of that reserve, an Awajún leader, Jessica Tsamajin, says her home was recently burned down as a threat from a corporation seeking to grab land that is not theirs. She emphasises how important these reserves are. Unfortunately, they are only set up when it can be proven that Indigenous communities are able to provide for themselves without accepting land destruction. Shiringa bio-leather production helps make that possible, securing the education and nutritional needs the community seeks.

Our land was once in danger of being cut down for profit, but we keep it safe and alive.

Rosalia Manuig Taan

“For the community, the bio-leather represents a source of sustainable income,” Tsamajin says. It is “a contribution to the conservation of the forests and the promotion of ‘tajimat pujut’,” which loosely translates to “wellbeing”.

Meanwhile, some 1,400 kilometres away in Peru’s capital Lima is Caxacori Studio, the material innovation start-up that Petsa and Taan work alongside to make the bio-leather. They work according to a conservation agreement, in which the community sets its payment rate and controls how the forest is used. Through this agreement, working only a few days a week collecting sap for shiringa bio-leather, an Awajún person can increase their income by six times the average for their community.

Jorge Cajacuri, founder of Caxacori Studio, says working with the Awajún people is an honour, and describes the collaboration as a meeting of their “knowledge of the land and trees” and Studio’s own “of material science”.

Many Indigenous Amazonian communities live alongside and work with shiringa trees, but do not currently create bio-leather. As such, there is significant potential for shiringa bio-leather production to scale and replace harmful animal-derived leather and unsustainable alternatives. This is a positive, but it must be done mindfully and led by the communities themselves. After all, the scale of fashion’s material use today is inherently unsustainable, no matter the material.

As Mozhdeh Matin, a Peruvian designer working with the “warm, rich and flexible” leather-like material says, “This material is a luxury. It should be taken slowly and with care.”